Hassan Rahim

For Viewfinder

Never on schedule.

Always on time.

Portrait by – NICHOLAS COPE

Ifirst met Hassan at The Living Room bar on Crenshaw and Adams. The comforting—at least to me—aroma of Miller High Life and carpet reached my nose as I walked up. This was all somewhere around the end of 2011 and "Watch the Throne" had just dropped. I can't recall who had connected us, but as the night went on obscure topics became less obscure around him, such as The Mid Night Car Speciall—if you know, you know. As “Who Gon Stop Me” came on, we talked about how the energy of that song was like being in a car going 248 mph, while still having another gear to go. I would then watch Hassan’s work do that exact same thing.

His artwork and creative process are snapshots of the speed of culture. It's both conceptual and accessible, which leaves you wanting more while simultaneously feeling familiar as if it’s been in your life long before that moment. His artwork is truly his own and he's as much of a cultural anthropologist as he is a designer, spending countless nights deep in the archives. I know Hassan hasn’t had an easy life, but he’s harnessed his past and used it to create a beautiful landscape that most designers aspire to create: a blurred image out the window of a car.

If you’re looking for Hassan, he’s currently somewhere in 4th with a whole other gear to go.

Founder of Commonwealth Projects, Total Luxury Spa, and TROPICS

By Mo Mfinanga

August 11, 2020

Estimated 19 minute read

Text edited by Dana Chang.

The following chat took place in late 2019.

Mo: When did you start to have an emotional connection to cars?

Hassan: When I was a kid, my dad used to drive me in his car and it had the sunroof and leather seats. It was the good E30. [both laughing] It was a stick shift iS, and he loved driving so the pleasure it brought him was contagious. From Orange County we would drive all the way to LAX and watch the planes take off and eat In-N-Out because there's one right over there. I was obsessed with all types of transportation, from aviation and trains to cars. I had car calendars, and I really liked Chevy Bel Air's and the 90s Impala SS'.

Hassan: My uncle also had a BMW, an E21. When I was in fourth grade, he was restoring it in the driveway at my grandma's house where I lived at the time. I basically watched him and helped from time to time put this car together. It was less about how they looked and more about how rad it felt being in them.

Hassan: I think it's funny because there's something interesting about Black kids—my age, your age—where we're just obsessed with classic BMW's and it's been ingrained in our heads. It was the whip to have before everyone wanted exotic cars. Rappers used to flex rather accessible cars like the AMG's or even Acura's, but now it's like you need a Bugatti out the gate. I just don’t find that tasteful. I hate to say it, but that was the golden era.

Mo: I agree. Funnily enough, I had a similar connection to cars through my dad. Growing up, during the dot-com bubble burst, my dad had a black E38, similar to the silver one in Tomorrow Never Dies. I was only three at the time, but I thought, “My dad had a James Bond car. Sick.” Every Sunday was almost a religious practice of spending hours together detailing his car.

Hassan: Being in New York I don't have a place to detail there, but I'm obsessed with it. When you're really in love with something you find out how to take care of it. It's like spoiling your partner. [both laughing] My YouTube algorithm thinks I'm a 55-year-old German dad that loves cars and detailing.

Creative direction and design for Jacques Greene’s Feel Infinite album. Photography by Mathieu Fortin.

Mo: How was the transition from a place like LA to New York?

Hassan: Initially visiting New York, I was always kind of awestruck. There's so much to explore and it was so fascinating to me before I lived here. When I would come visit from LA, I would be enamored by the amount of things you could do on foot and the people you run into—the way time slips differently here. But when I moved here, I realized on the day-to-day basis people don't roll like that. You have to have your safe haven, or quiet place, and you can pop out whenever you need to. There's not a lot of people I know that live in Manhattan long term, it’s too chaotic. Everyone's in Brooklyn.

Hassan: So, I became really familiar with a rhythm that worked for me, and started understanding how you can navigate this place on a day-to-day basis. And most importantly, I've realized I really don't fuck with winter, so I think every year I'll be living in LA for three months: January, February, and March. I love seasons changing and the way that affects everything you do, but I also realized that you don't have to put yourself through all that. [both laughing]

Mo: How has your relationship with New York changed?

Hassan: To be honest, it changed a lot because I lived with a partner when I moved here, but we ended up splitting up and I got my own place within the first two years of living here. Living alone in New York is interesting because as busy of a city as it is, and how much stuff is going on, you can also very easily slip into an antisocial pattern.

Hassan: In LA, you're in your car a lot of the time so you're by yourself a lot by default. But here, you're on the train, an Uber pool, or on a crowded sidewalk, but it's actually more isolating being around complete strangers. As I live here longer I'm realizing that I'm not doing all the cool Manhattan stuff and taking advantage of the things people see New York for. I'm just in Brooklyn chilling. [both laughing]

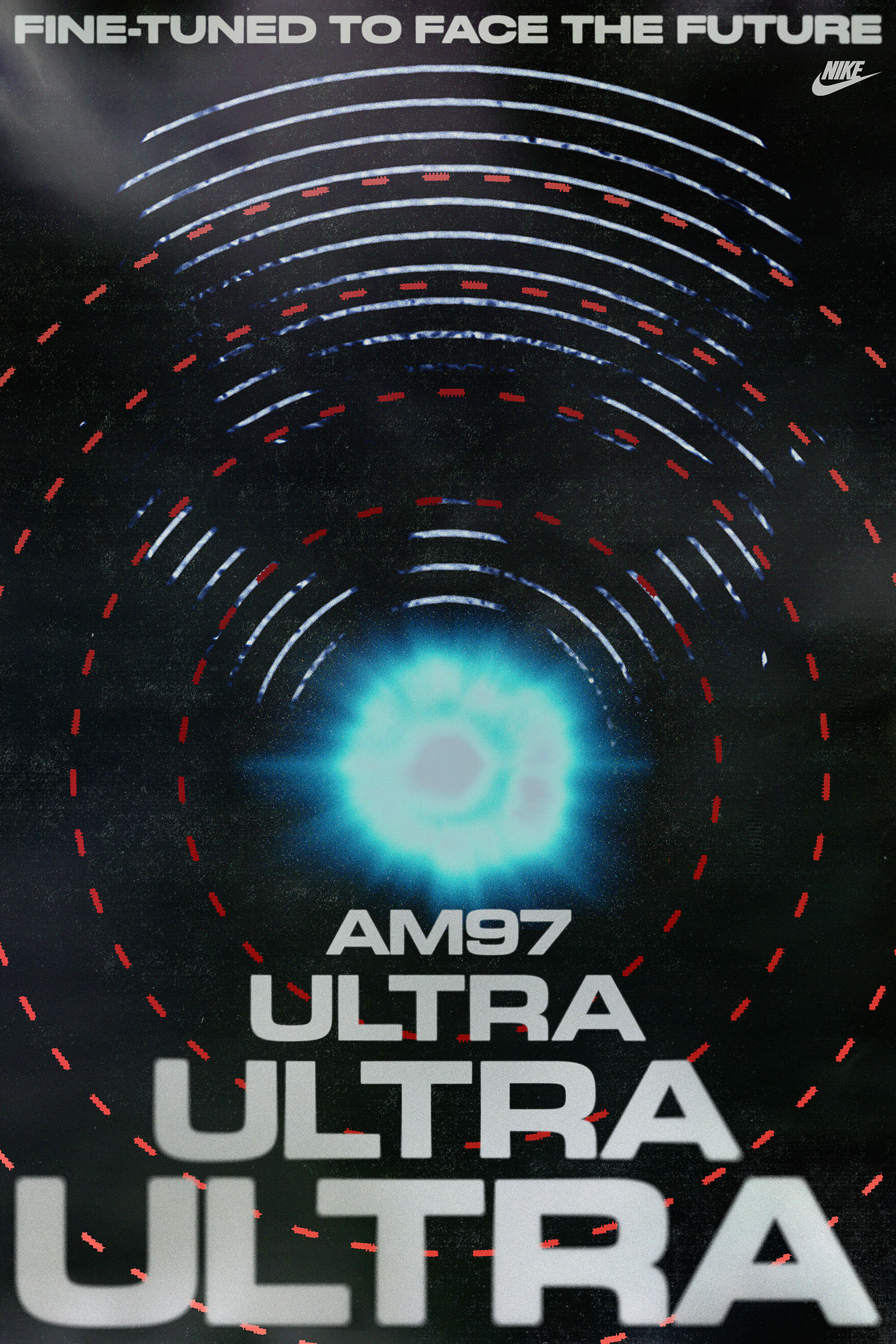

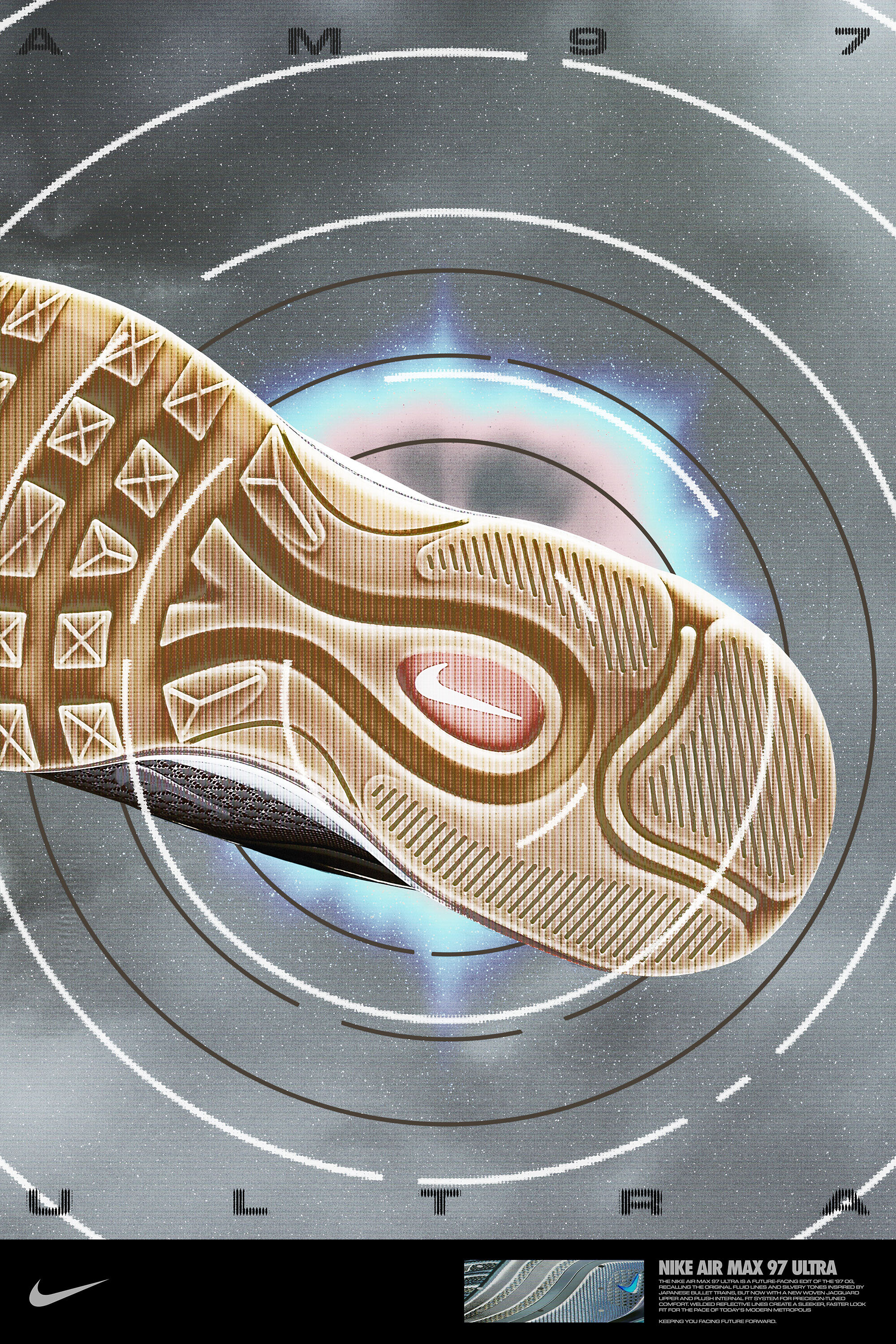

Two of ten 3M rave posters created for Nike’s Station 97, a subway station takeover in NYC celebrating the underground heritage of the Air Max 97.

Mo: I want to discuss your talk at Us by Night. How was that experience?

Hassan: Rizon Parein, the director of Us by Night, invited me to talk last year but I was in a little bit of a different headspace. I wasn't really feeling like I was ready to do a lecture. I was still recovering from a few really crazy projects and I also was in the midst of figuring what my next steps were in understanding my work and talking about my work. At the same time, their event was on Thanksgiving, which despite being a bullshit holiday, is a very important time for families to spend time together. I had to tend to a Thanksgiving thing so I bailed, and when you miss out on opportunities like that you kind of have this fear that you blew it and you'll never get it back.

Hassan: But sure enough, he was like, “Yo, you gotta do it this year. What's up?” He told me that the people who actually have a story that others need to hear are always the first to turn it down. I was stressing out because I'd never spoken on a stage before in my life. So it felt like a responsibility for me to do, especially with the level of visibility I have as a Black designer in a predominantly white industry. I thought about all the young designers of color who message me daily and said fuck it, let's go. So I got there and Antwerp was chill.

Mo: How many people were there?

Hassan: 800 to a 1,000 in that room.

Mo: Oh, fun. [both laughing]

Hassan: Sure, great! [both laughing] I was freaking out but they made me feel real confident about it. On top of that I spent many months watching TED Talks and a bunch of other lectures, and learning techniques I felt like I lacked. But when you really look at it, when you are your most comfortable self—at dinner with friends for example—you have all that stuff. You have the charisma; you have the gestures; you have the way of words.

Hassan: They say it helps to imagine everyone in their underwear, but that definitely doesn’t work for me, but in a similar manner I found my own way of getting comfortable on stage. A glass of wine always helps, too. [laughing] But it was great, man. I spoke mainly about how I got here because, to be honest, a lot of people do a lecture, especially in creative industries, as more of a case study on all their projects. I was like fuck that. I started with a 30-second reel that was cut to a crazy punk/techno song by Debby Friday as a teaser, then shifted gears and explained how it would be a disservice to talk about my projects without telling you how I got here because my path is not linear.

Hassan: I started with explaining how I grew up in Orange County, in and out of group homes and meth head motels. Skateboarding basically saved my life and kept me out of trouble. I lived in a group home for a while and that's when I had access to a computer for the first time. Well, actually not the first time, because I was always taking those AOL free 90-minute CD's since I was 13, but that was back when 56k happened!

Hassan: The group home had DSL so I was browsing on another level. I downloaded Soulseek and discovered this whole new world of stuff that in Orange County we didn't have access to. And then I downloaded Photoshop. I wanted to make skateboard graphics, so I talked about how I got started doing that, how I had put some of my work on Myspace, and then I talked about moving to LA and just partying there a lot. [laughing]

Mo: When did you move to LA?

Hassan: When I was 18. And the way that I moved to LA was that I was doing t-shirt graphics for some skateboard companies, and one of them was Diamond—who is now a full-on streetwear company, but at the time it was a skateboard hardware company. I did a really popular shirt for them that was an Iron Maiden rip-off and that shirt basically blew up at the time. So then I dm-ed them like, “Yo, I don't really know you and you don't know me but I gotta get the fuck out of Orange County,” because my dad was getting evicted and shit. And I was like, “Can I sleep on your floor?” He was like, “Fuck it,” [both laughing] so that's how I got to LA.

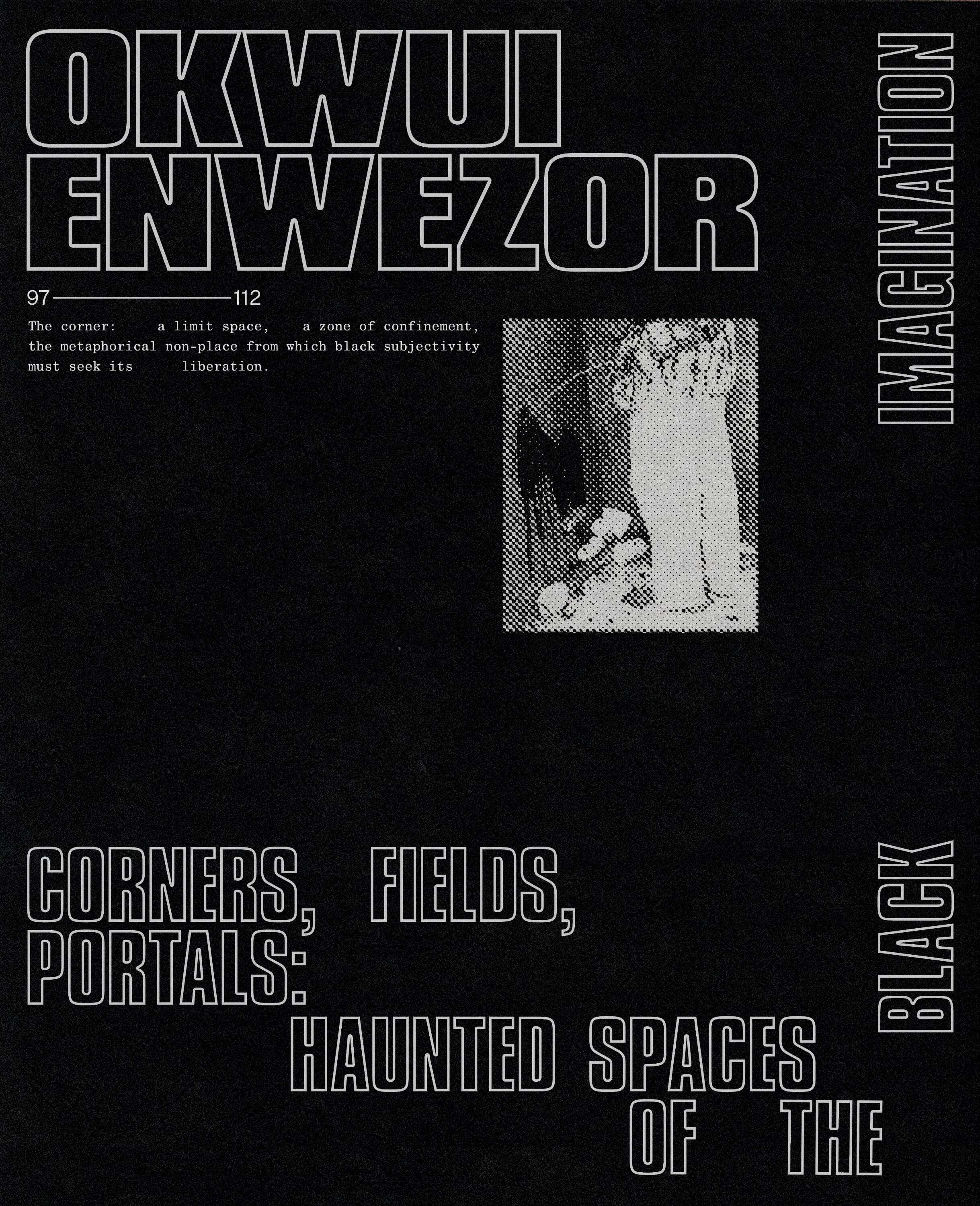

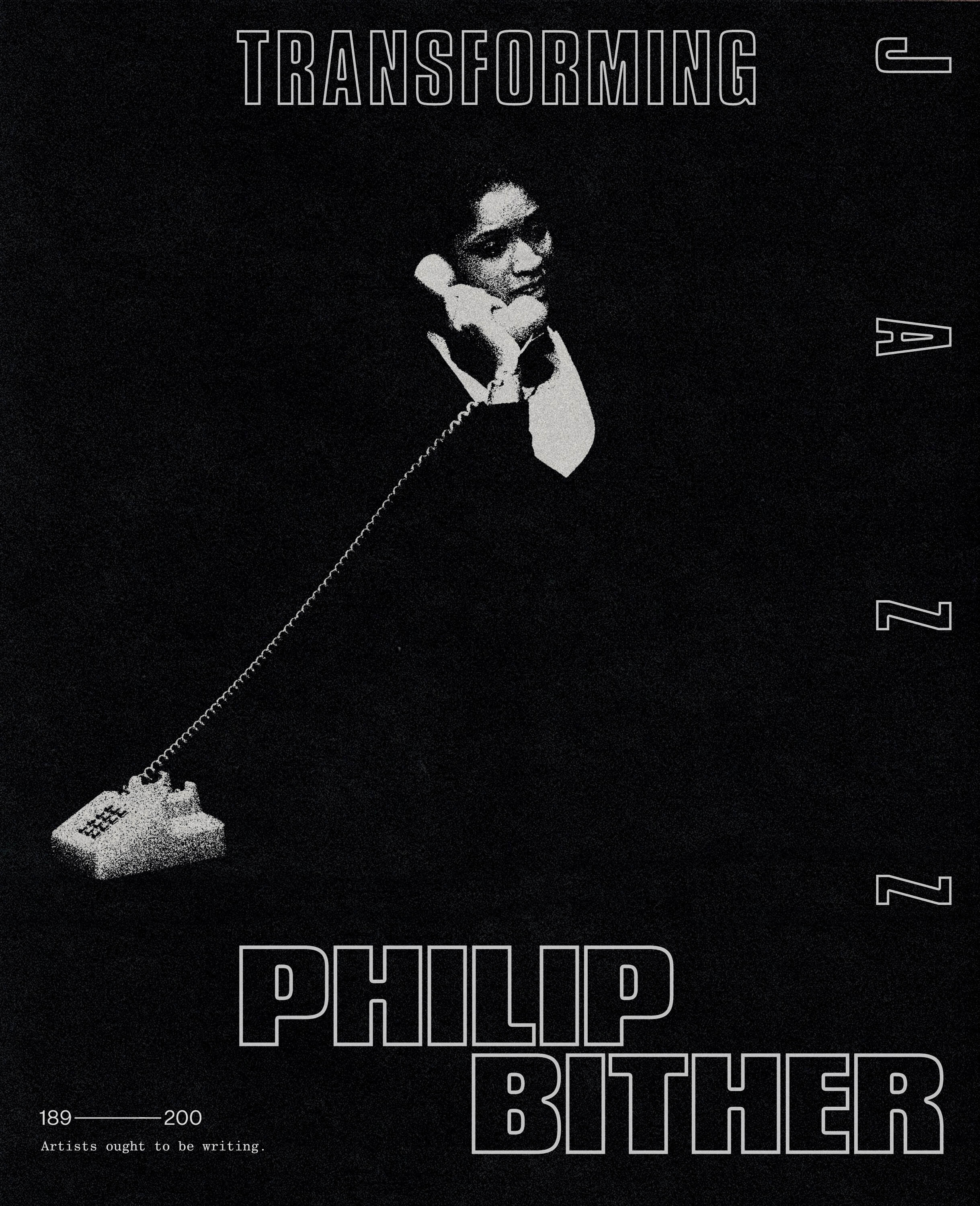

Chapter header treatment for Jason Moran's monograph designed by Hassan for The Walker Art Center.

Hassan: So I talked about some of my earlier work where my influences were dollar bin records and collaging stuff. I treat my work more like J Dilla or Madlib; I'm always chopping a drum or a snare, I love sampling. I started showing some of my early collage works, which nobody has seen—which is funny—as well as the references from them. Then I fast forwarded to when I lived in Philly for a year-and-a-half at a really terrible company with a job that made me want to kill myself. And I openly talk about depression and feeling stuck, wondering what I was doing there, and how it's all about politics and you can't really trust anybody in those environments. The city sucks, too. Sorry. Shoutout to my friends who rep Philly, though. But yeah, sorry, it sucks there. [laughing]

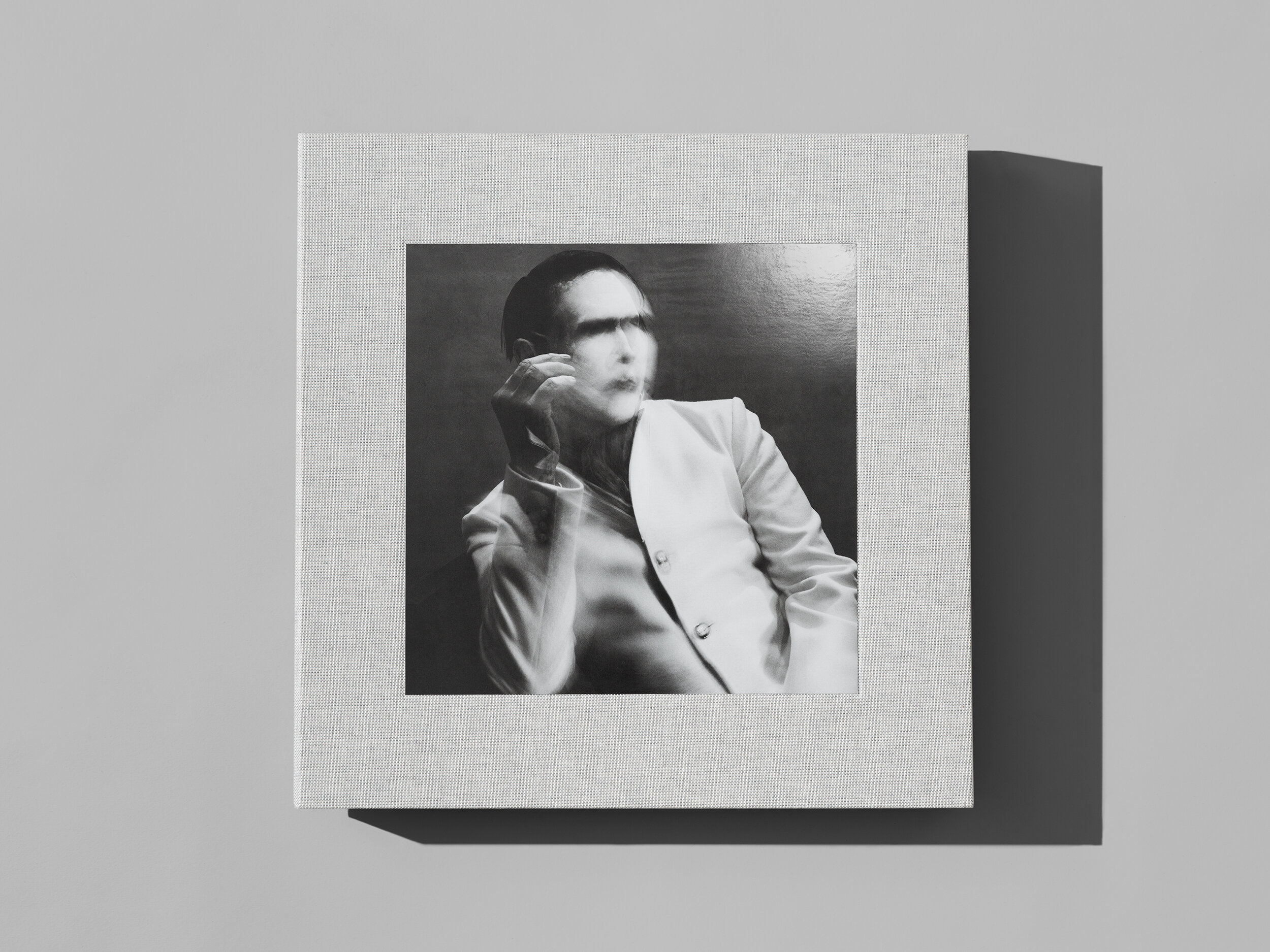

Hassan: From there I talked about how I quit without a plan, and within a week or two of quitting, I got a phone call to work on a Marilyn Manson job. That project gave me so much of my confidence back. I started trusting my judgment again. People were always telling me I'm not shit because I didn't go to art school. And I was like fuck that, fuck everybody.

Hassan: I don't get too political but grid systems are designed to keep Black people oppressed. I grew up within many types of these grid systems, so I talked about design grids and the books that you read in design school and me completely rejecting them. I went into that, showed some more of my work, and ended with a motivational quote from Ghostface.

Art direction and design for Marilyn Manson's The Pale Emperor album campaign.

Photography by Nicholas Alan Cope. Creative direction Willo Perron.

Mo: One of the things I'm interested in talking about that you just mentioned was growing up in group homes. What was the definition of community to you in that landscape?

Hassan: It's a hard question to answer but all I can say is that community for me came from skateboarding. Being in a home that wasn't safe to be in, growing up under those conditions, and then eventually being taken away from that home and being put into a group home... I think finding community for me was always skateboarding and music—skating ledges, staying up late, or going to punk shows. That was my community. It had nothing to do with my living conditions; it was always outside of them.

Mo: In hindsight, what do you feel led you towards Philly? Was it you trying to get out of where you were?

Hassan: It was never really a decision to go to Philly; it was a decision to take a job and that job was there. I got offered a really good art director position at a company and I was launching a very specific division for them as an art director. It sounded like a really great thing, but when I got there it was a totally different thing. My partner at the time got hired for the same company and we moved there together, so I wasn't there totally alone.

Hassan: I think LA was a little stagnant for me at the time. There's a lot more stuff happening in LA now, but it's still a pretty small creative community. If I were to move my studio to LA now, most of my clients would be from New York or Europe. But had I not left LA and expanded my network, I'm not sure where I would be at right now, so I'm really glad I did. Moving to Philly got me to New York, and being in New York got me all around the world.

Mo: Speaking of LA, I recently met Daniel from Total Luxury Spa, and it was nice seeing the sense of community being inserted there, especially in the context of your involvement there.

Hassan: I mean, Daniel's family. He's maybe the one person that I can always trust. It's funny because going back to your question about how my relationship changed with New York—I don't trust a lot of people here. [both laughing]

Hassan: I don't open up easily so mutual trust becomes a weird stalemate sometimes. But Daniel's been a friend of mine for 10 plus years and I can always rely on him. We keep it a hundred, a thousand—a million—with each other and that's why I love to collaborate on Spa. Daniel is always about giving back. I've actually never heard anyone say a bad thing about him. What he does with the neighborhood is awesome and I just love being a part of that.

“I just moved through life with the notion that I’ll never win them over. ”

Photo illustration for The New York Times about the challenges of being Black in America, featuring Olympian Jackie Joyner-Kersee.

Mo: I want to rewind back into your formative years again because I'm curious about the responses from family and friends when you decided to pursue this career.

Hassan: I think everyone seems really proud of me to be honest. I don't come from the worst conditions on the planet, you know. There's real poverty out there, homelessness, refugees; people with extreme issues. But where I am from, a lot of people don't make it to where I do. So it's really nice when people are proud of you because, yeah, there's a lot of my friends that are dead, in jail, struggling with addiction, or struggling with serious psychological trauma. It's nice when people acknowledge your motivation and drive to do what you did with the hand you've been dealt. Even if things plateau for me career wise, my life is still a success story to a whole other world of people outside of my industry peers and I’m very satisfied with that.

Mo: Since the lecture made you formally look back at your work, what did that reveal to you? And what has it indicated towards future work?

Hassan: One of the biggest slides in my presentation said in bold type, “What the fuck is success anyways?” I talked about this six figure job I had at this company and how none of that shit mattered, actually. It wasn't work that touched people; it wasn't work that meant something; it wasn't from the heart. I'm super emotional, I wear my heart on my sleeve. So if I connect with people, it has to mean something. The next slide after that was about scales and illusion.

Hassan: People can see you're working with a big name brand, or doing some huge global project, and believe this is the way to measure success, but it's an illusion. Some of the most important projects I've done have been as small as a little t-shirt, logotype, or graphic I did, like the illustration I did for The New York Times of Jackie Joyner-Kersee. There's really important work where maybe I got paid $100 or zero dollars, but they've paved the way for how I think and continue to create. I think that's what I learned throughout looking back at my work.

Hassan: And while it definitely is nice to work on really cool stuff for big brands, I ended the presentation on that New York Times illustration, because it's one of the more important projects I've done. I think if I can choose to navigate in a way where everything has that level of personal meaning, I'll be extremely fulfilled.

Mo: I think that's a natural impulse for most people who work in a creative atmosphere. We're in a medium that's supported by our beliefs, interests, and emotions. You can't fake that shit. The circumstances of our world are getting louder and because of the accessibility of these mediums, you can start to see the two have a dialogue.

Hassan: Totally, and I do think it's a natural instinct for artists to gravitate their work towards a meaning, but you may be surprised, because when you start working in the commercial and corporate spaces, man... Maybe some occasional projects can have a higher purpose, but the rest is just work. That's where you draw the line sometimes because everyone's gotta get paid. I wish I could make illustrations like that NYT one for a living, still make rent, and still pay for the gas in my 630CSi. [both laughing] We always have to walk that tightrope between art and commerce. Everyone's trying to bridge that gap.

Hassan: You know, I often get into debates with these critical design theory purists who are stuck in some long gone utopian ideology that design must strictly serve this greater cultural purpose. In their heads, they see me as an example of the “self serving designer-auteur, obsessed with ego and clout, all about a buck,” but they don’t realize they’re preaching to the 12-year-old Black boy with holes in his shoes, eating government cheese with day-old Wonder Bread, watching Michael Jordan drop 55 at Madison Square Garden. My idea of a higher purpose comes from much different conditions. Sometimes the thought of making up for 18 years of being broke and struggling by having enough money to live comfortably is enough purpose for me—and that’s ok.

“Make sure you’re not just delivering what’s asked.”

Identity for BLKNWS, a project by artist and filmmaker Kahlil Joseph. An ongoing development with Lee Harrison.

Mo: Are you aware of the narratives weaved in your respective design community?

Hassan: It's complicated. A lot of my early struggles were with trying to fit into design but not coming from a design education. I've kind of always been an outsider to all of it. I think my relationship with the design community is complex because I wasn't really accepted for a long time. So am I in tune with it? Somewhat. But it's hard coming into design from my lane, and even having a conversation with some designers and talking about the type of stuff that got them started.

Hassan: Everything I talk about with most of my design peers is from a super academic lens, and I realized over time that I just have a different way of doing things. Growing up Black in America is often constantly dealing with imposter syndrome and assimilating with your surroundings out of survival, but I decided to just say, “Fuck everybody.” And I think me saying, “Fuck everybody,” helped me get to where I am. My mindset went from “I must get these people’s approval” to “I'll never get anyone's approval.” So I just moved through life with the notion that I’ll never win them over. That’s when my survival instinct kicked in. I decided to let go, and just said, “I'm just going to do it my way.”

Hassan: Now it's like, cool, you've proved yourself, and here we are all at the same table. But how much do we have in common outside of the table itself? It's not said in an elitist way. But it's a story that most young Black kids could relate to as well.

Mo: 100-percent. It’s a mechanism I’m way too familiar using, but I wonder how we can minimize or even eliminate this approach for future Black artists?

Hassan: One thing that was really important to hear from a young designer recently: The very fact that I’m here and visible was enough of an example for them to pursue this career. I do think that the more of us who break down the walls and simply circumvent the gatekeepers are living proof-of-concept that you indeed have a seat at the table. I know that sounds like the bare minimum, but it’s still new for me, and I’m still working on ways to continue uplifting young Black artists. I just got here, dawg! [laughing]

DJ R.I.P. — My Mind Gone (Original Mix)

India ink, marker, paper, pigment on panel

42 x 42"

2016

Mo: Is there anything in design that you hope to find the answer to?

Hassan: This isn’t the most awe inspiring answer, but I would like to create a form of passive income that isn’t tied to creative services. Financial freedom is the primary way I can continue to keep my work pure. Everyone’s different but I can’t see myself nitpicking over client revisions when I’m 55-years-old, I don’t see it as sustainable in the long term. That said, I eventually want to focus more on selling artwork, prints, or find my way into the products sector.

Hassan: I realize a lot of people my age start a creative studio. It usually starts out super radical, but at some point you start accepting certain work to pay for your team and keep the lights on. Sometimes those big projects are six to nine months long, and that actually takes a pretty big toll on your brain. If you're working more than half the year on something you're actually not excited about, it changes the way you perceive the work as a whole. That's why it's important to be super picky. And after 10 years in the game, I believe that only comes with financial freedom. I want to be able to be picky and have the bills paid, you know? That's what everyone is trying to crack.

Mo: What has your practice influenced in your life?

Hassan: “It doesn't have to make sense to everybody.” That's where I come from now, and that's where that Ghostface quote came from.

“I don’t give a fuck if you don’t know what I’m talking about—this is art. When you go see a painting on the wall and it looks bugged out because you don’t know what the fuck he thinking, because he ain’t got no benches, no trees there, it’s just a splash. The nigga that did it know what the fuck it is.”

Ghostface Killah, "The Wu-Tang Manual", 2005

Hassan: Explaining everything and making everything face value for it to be easy to digest is not my business anymore. I try to go further and further in the hole of concept, or that hole of what things look like in my world, and how they feel to me. That's how you break new ground on a personal level. Make sure you're not just delivering what's asked.

Mo: Do you think that's weaved into the purpose of your work? Or simply put, what is the purpose of your work?

Hassan: Oh, man! [both laughing] Yes, I believe it's weaved into my work. My style is weaved into my way of thinking, and is weaved into the clues that I leave for people to ask questions about what they're looking at. “What is the purpose of my work?” That’s the big question you just asked me. “What are you trying to crack in the creative industry?” A lot of people have a purpose in their work, and I think my work serves a different purpose every time I make something. That's the difference between art and design, I think.

Hassan: Not all artists serve a purpose. Yeah, there's obviously artists that are working in ways that are helping communities or bringing awareness to issues. But I try to strive to find new purpose and find new meaning with every project I do. I rebuild my toolkit every time something comes in front of me. I reimagine what that is. For instance, maybe it's not a toolkit. Maybe we don't need tools. Maybe it's a car detailing kit sometimes. [both laughing]

Hassan: The purpose is always different, so sometimes what's required is a maybe just different way of defining purpose. 〄

Discover More

- Viewfinder

Conversations that explore the risks, ideas, and experiences of ones practice.

- DIGITAL DISCOURCE

Live chats between artists that share thoughts related to their practice.