Mo: What’s a pleasant surprise in your role as a photo director at The New Yorker?

Joanna: There are fewer opportunities for photography in this magazine because there are no photo covers, but it seems like photographers really want to shoot for us, which I guess I shouldn't be surprised about! [both laughing] That's been great.

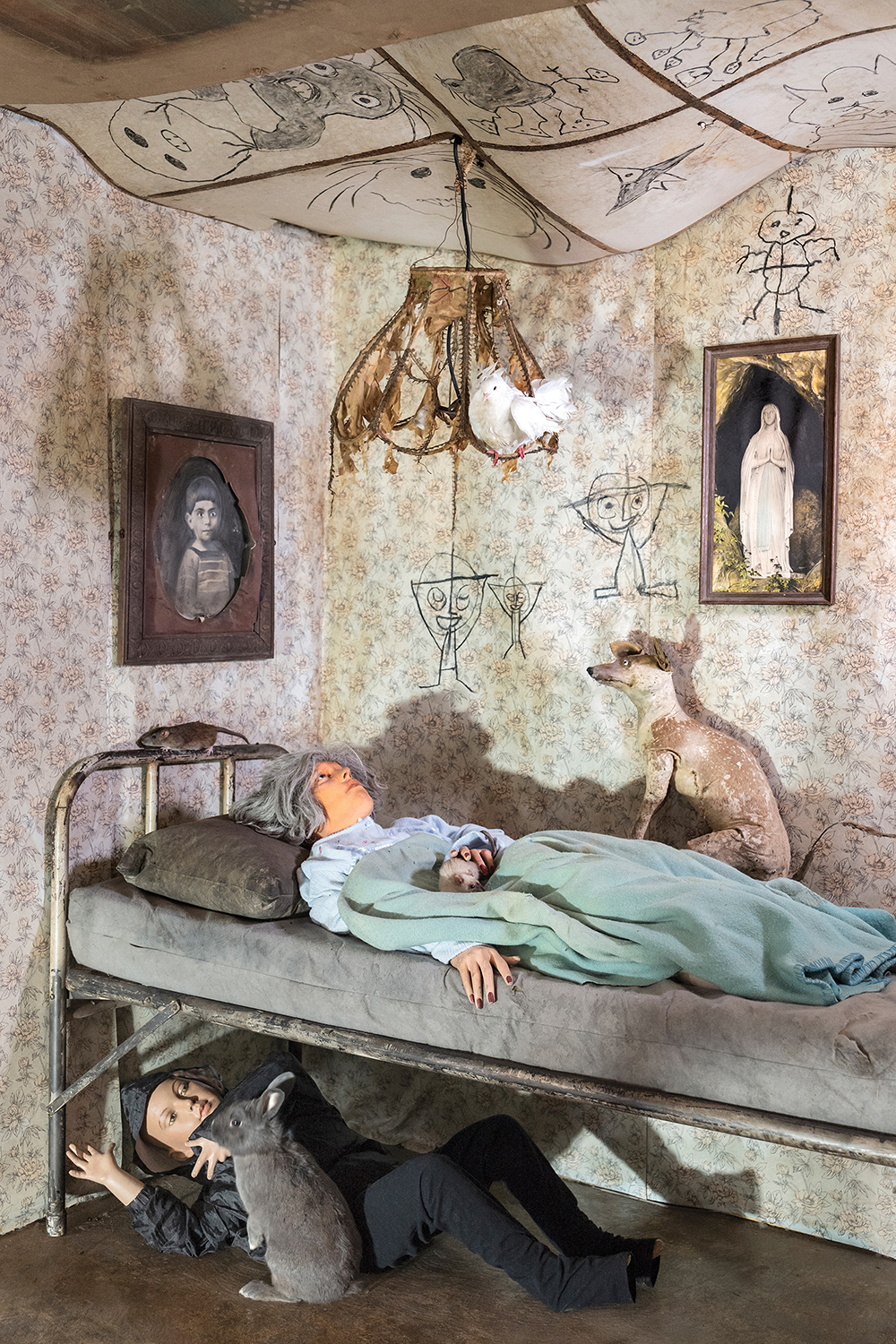

Joanna: Even though our page layouts haven't changed much since the magazine’s early years, it is amazing to me how much visual variety our layout templates can stand. We're able to assign lots of different kinds of photographs; the photos should be a visual indicator of the variety of topics covered in the magazine. There's serious journalism, there's humor, there's culture pieces and reviews, and there's fiction. One challenge: We have so many portraits! Can we look at a story, and figure out a way to assign a photo that isn't a portrait?

Mo: In 2019, what do you feel like one of the biggest responsibilities you have as a photo director?

Joanna: That's a good question. I have to think about that for a moment because there are so many. It's about broadening the tent and bringing in more new and up-and-coming photographers. That's one of the things I learned from Kathy. She's never resting on her laurels; she's always searching for new photography and new ways of looking at the world. And I think that's something that I try to remind myself that we need to do all the time. I think that's really important right now.

Joanna: Another is trying to figure out how to tell stories in a visual way. That's not necessarily a new thing for 2019, but there's a way that images can have an impact, even in a writer-driven magazine.

Mo: Is there anything that concerns you heavily in editorial photography?

Joanna: I think it's harder and harder for photographers to make a living. It's something as photo editors we have to keep in mind. It's just tough. There were earlier periods when photographers could make a decent living in editorial photography. And those days are gone. On the one hand, there are so many images on social platforms and websites, which is really exciting, but on the other hand, because images and image-making is so accessible, it makes it harder for photographers financially. It's something I hear from photographer friends and photo editors. What do you think about that?

Mo: In my very limited experience, I share the same sentiment that money is harder for photographers to come by now. What I've been trying to figure out, amongst contemporaries and friends is, What's the catalyst behind this climate? Unfortunately the infrastructure of companies and magazines make the payment process for freelancers strenuous, especially when the budgets are smaller yet the demands are the same, if not, higher.

Mo: But editorial work can provide more creative freedom to a freelancer and accessibility to higher figures than other avenues, generally speaking. Editorial photography isn't going away, at least to my knowledge. People still want to shoot for The New Yorker. People still want to shoot for The Times. But at what capacity can we sustain within the changing, decentralized climate of photography? We're all trying to figure this out. The burning question for most is, What's the next step?

Joanna: I honestly I wish I had the answer, but I don't, Mo. Every major city in the country—and most smaller cities—had a daily paper with staff photographers and now that's no longer the case. There's less editorial work, frankly. On the other hand, now the barrier to entry is lower—because of the rise of digital photography and the internet. So young photographers can make and publish projects on their own platforms, and photo editors can find them that way, so that's extremely exciting.

Mo: I remember talking with Chris Maggio—a brilliant photographer—about how photography is such a young medium. I mean, compare its lifespan to paintings and it seems like an infant. We're seeing it change rapidly which is scary because I'm going to naively assume that the ‘80s and ‘90s had a pretty straightforward and predictable pace of photography in culture and the economy. So not many photographers were battling the hills we're climbing now. And think about the economy. Advertising is one of the first industries to be affected when things are good or bad in the economy. So photography takes the fall in those situations. But what do I know! I'm six-years-old! [both laughing]

Joanna: You're 21! I didn't even know what was going on when I was 21. [both laughing]

Mo: So what’s something you want to explore more of in the near future at The New Yorker?

Joanna: Integrating photography and video. Learning to shoot video is one of the things that photographers have realized they need to do, for both financial and creative reasons. We've seen an explosion of interactive projects integrating still photos, words, videos, maps, and everything else. When it comes to the visual stuff at the magazine, we're underdogs in some sense because most of the emphasis is on the writing.

Joanna: We have a small, terrific interactive department and the photo team works with them and our design team on different projects—that has been really fun. In general, I love seeing what other publications are doing with interactive. The Times is a wonderful platform to witness how photography can integrate with video—I love it. Some of the sports platforms are doing great interactive work: Bleacher Report, The Ringer.