Nick Waplington

For Viewfinder

Trusting the journey.

Portrait by – MO MFINANGA

Nick Waplington’s book, The Living Room, (1991) exploded onto the fine art book scene with the same fervor as a Beatles or Stones album. It was a sensation. For art photography books, that was unheard of. An invention of a new type of photo book that superseded the stale glossy and boring retrospectives of the '80s. There’s an intimacy and tenderness that echoes W. Eugene Smith, Larry Clark, and Nan Goldin.

The Living Room was the work of a painter searching for the unexpected—something that you and I would not see—and that is Nick’s strength. Avedon likened his work to Brueghed or Rubens.

Over the years, the work has been wonderfully diverse. Truth be told, Nick is a compulsive book maker, and how great for us. I personally always look forward to seeing where his eye will take us next.

Photographer & Filmmaker

By Mo Mfinanga

May 15, 2020

Estimated 17 minute read

Image above from 'Living Room'.

This chat took place in Lower Manhattan, New York City, mid 2019.

Mo: What has New York looked like over the years?

Nick: Obviously before the Giuliani cleanup it was kind of more fun, but before the Giuliani cleanup I was in my 20s. [both laughing] Now, 25 years later, I'm 50. I know that young people are still having fun and going out and doing things, but when I was in my 20s I would be going to illegal parties in gambling dens around 42nd Street and now people are out in Ridgewood, Queens going to warehouse parties.

Nick: It still exists but it's not really in the city anymore. But I'm sure that there are subcultures in the city. A friend of my wife has a son who navigates all the underground tunnels around the city.

Mo: Have you ever been to them?

Nick: No, but I should do it with him. There's people living down there and all sorts of parties and weird things going on. It's not necessarily subway tunnels but there's a lot of different tunnel systems apparently.

Mo: Do you feel like you've discovered any other new things in the city?

Nick: No, not really. The city is extremely expensive so it makes you work hard. The work that I make here tends to be paintings. If I'm making photo-based work, 99-percent of it is made elsewhere, and I come back here to go through it—it's another part of the process. My wife teaches at Columbia University so we're based here.

Artemis II

Mixed Media on Canvas

60 x 50 inches

Nick: New York is very good for getting my head down and working, though. London, for me, has too many social life possibilities. There's a going out culture there that I don't have here, which involves the pub and music, whereas here it's different. America has a very work-oriented culture. On the other hand, Merry England—as we call it—is “merry” because people are having a good time in a way that people don’t here. People have to work. In England, people are like, “fuck it.”

Nick: When I was going to my show in Berlin, I stopped in London for the weekend and I was in this restaurant on a Sunday night and it was 10 o'clock, and then suddenly they decided they were going to get the decks out. The next thing I know, I'm sitting at this restaurant at 4 or 5 a.m. and people have come from all over. The street is packed outside the restaurant, loads of people are on drugs and there's a fucking rave going on, yeah. Three or four hours earlier there was no possibility of that even happening. You don't see much of that here. People have to go to work to earn their money here. America is very good at kind of making everything expensive to keep people working.

Mo: The price of comfort in America seems to increase whenever you glance at it.

Nick: Yeah, they've instigated a kind of regime here that people have to keep working to live. In Europe there's still space to live for less money and have time. They've taken time away from ordinary people here. They don't want people to have time to think here. America is about making money, consuming shit, and then dying. [both laughing]

Photo from ‘Living Room’, 1991.

Photo from ‘Living Room’, 1991.

Mo: Is there a structure built around what projects you decide to focus on? Or is it a spontaneous process?

Nick: It changes with time and then there are older and newer things and looking back at older things and trying to contextualize them with newer things. I had a show opening in Berlin last week, and while I was there I printed two books at a place called Optimal which is north of Berlin. That was a good bridge to the end of something and that made me think about what's next after these two projects that are finished. They've gotten to the book stage which means they're done and [so] I can forget about them.

Mo: Do you have projects where you complete them now but you know that you want to leave some room to revisit in the future?

Nick: [Nodding] There are things in the '80s and '90s now that you can go back to and you find new and different things, so that's happening to a certain extent at the moment. I'm a sole practitioner. I don't have anyone that works for me, deliberately. So if I work six-and-a-half days a week then I can only do what I can do in a day. I don't want to get away from the work to the point where I'm delegating things out of my control, other than designing books.

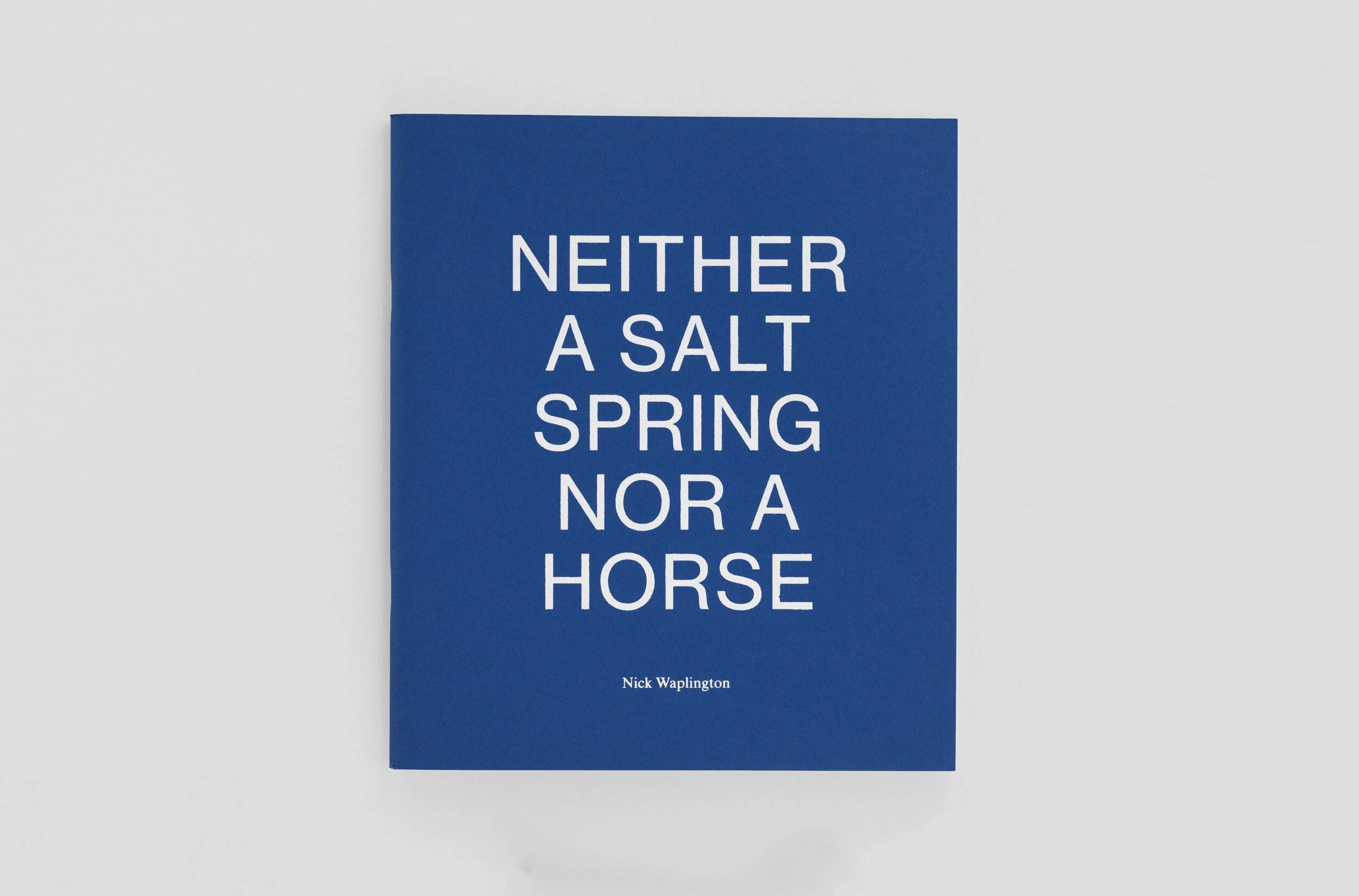

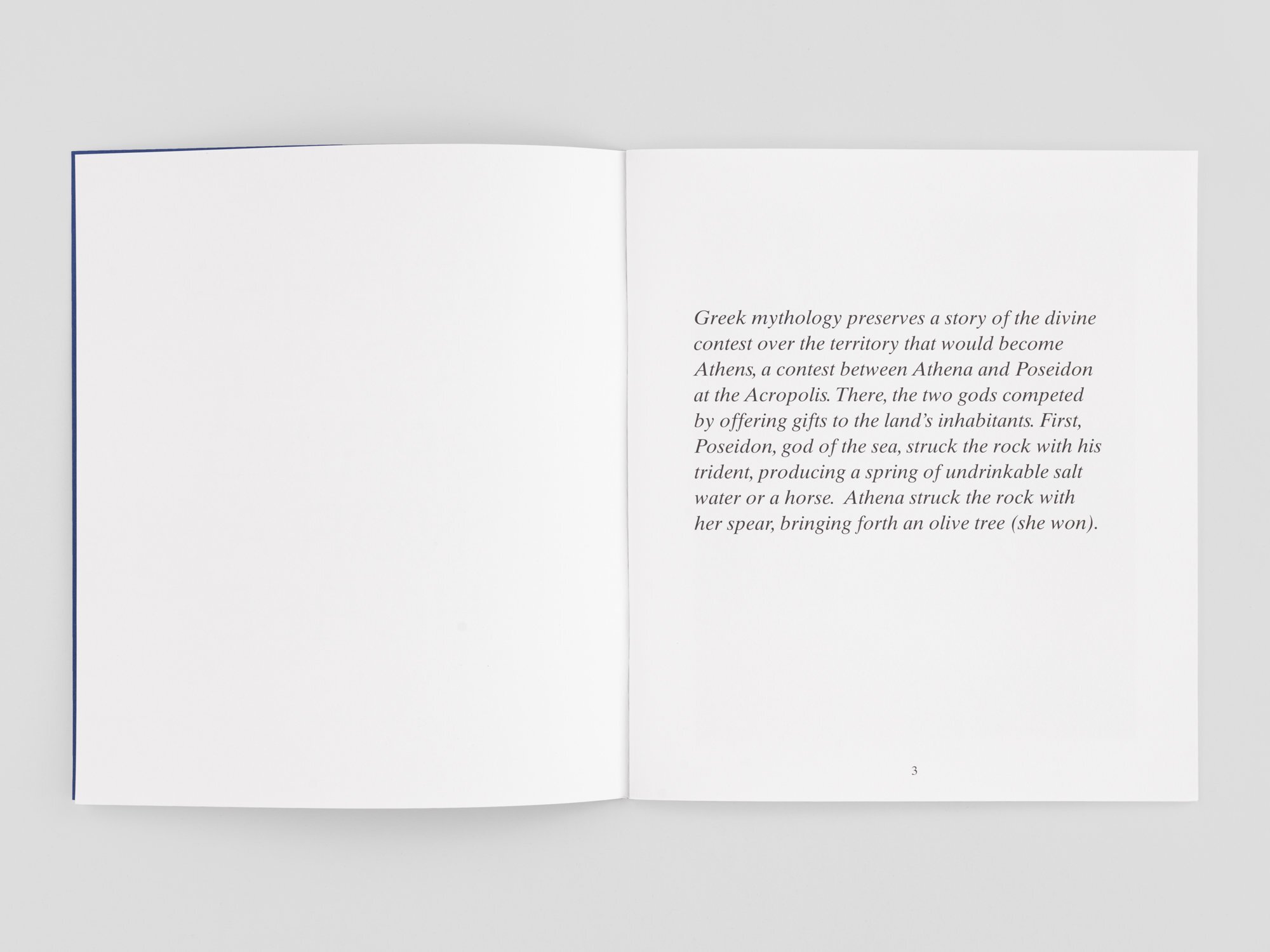

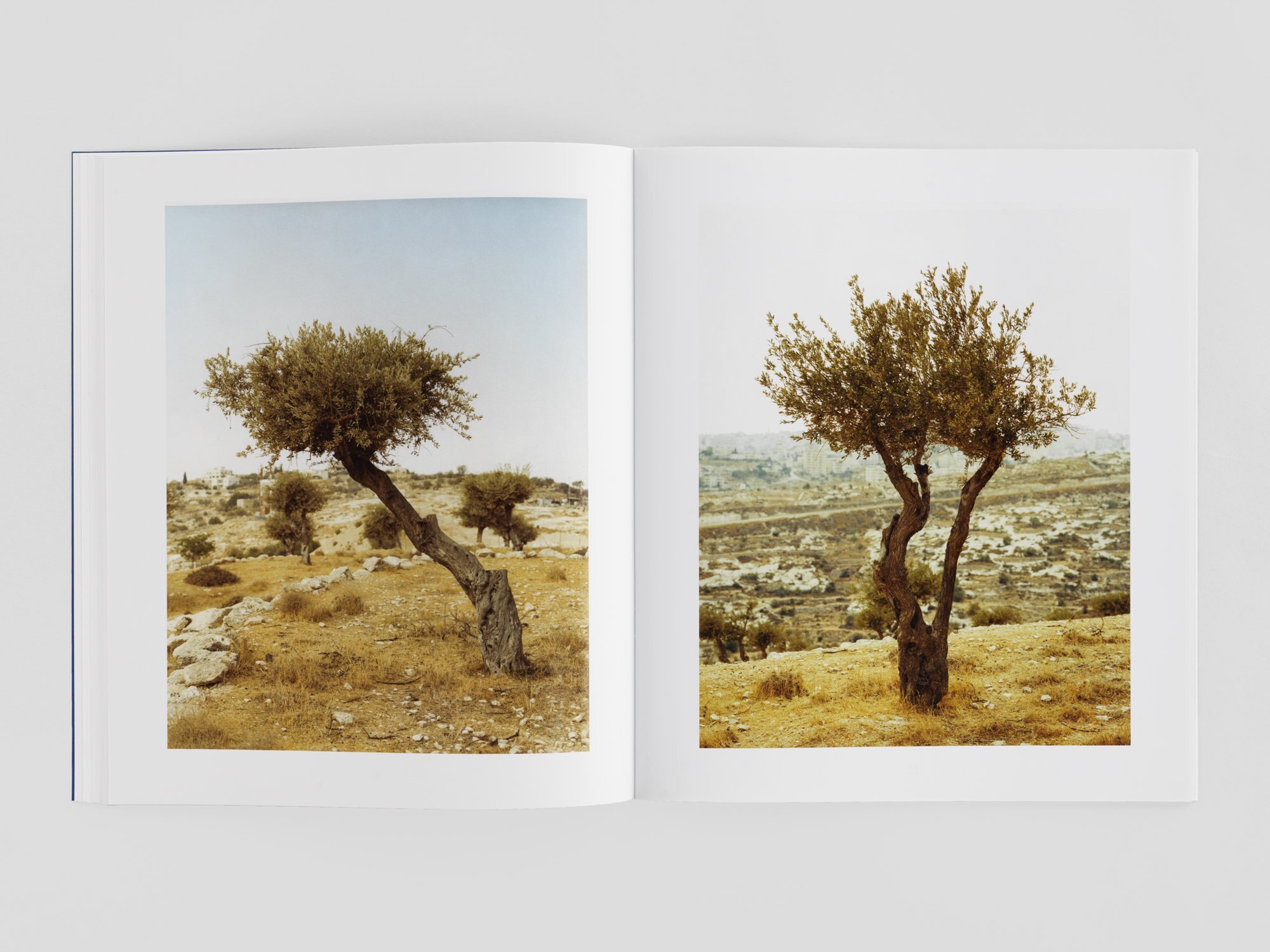

Mo: You've done a great job collaborating with the right designers, like Pacific, for Neither a Salt Spring Nor a Horse. [pictured above] What did you feel was the objective you wanted to portray through that book?

Nick: That book was interesting to me because I combined paintings and different kinds of photographs. I don't want to give it away but I can explain what the book is about. Basically, there are too many people living in Israel-Palestinian—it's overcrowded—so that's what it's about. Those biblical era olive trees are being uprooted to build more housing so young women, like the women in the book, can have ten kids that can have ten kids that can have ten kids. I got to know those girls while I was living there and I liked them a lot and was thinking about their future. They're Haredi, Jewish religious girls so getting to know them as a guy was quite weird.

Nick: Thinking that they were 17 or 18 when I took those pictures, are they going to spend their lives making babies? So I was thinking of the trees and threw the paintings of the landscapes in there to intertwine the three things. It's an experiment, you know. It's kind of open to interpretation as well even though I'm explaining it away right now.

Nick: A lot of photography tends to be very literal—a spade is a spade. Or it seems to be about something extremely vague that you can't get your head around. So I tried to talk about political, real things but within a slightly ambiguous manner. It's my modus operandi and always has been.

“Collaboration is good if you agree to do something neither of you have done before. ”

Mo: The intersection of mediums in your practice has been interesting to witness. For photography, especially those starting to digitally explore it now, it's easy to forget the tangibility it can provide.

Nick: Yeah, a lot of photography operates in confides in photography that already exists. People want to make a photo book that looks a bit like what a photography photo book that already exists. Obviously it's easy to make a book nowadays, so most of them I find extremely dull. Sometimes I wonder why I'm still making photo books. [laughing] They said that to me at the printer they can't believe I'm still doing this.

Mo: What is something from your work in the '80s that has recently surprised you?

Nick: Finding pictures that I have no memory of taking is kind of interesting. I've taken a lot of photos, so if I get out a file of photos from 1985 then I can't remember taking quite a lot of the pictures I'm looking at, at all. I found all these films from 1984 when I was walking around the old 42nd Street and then I remembered what I was doing then, walking around with my 6-by-9 taking pictures of whatever was going around there.

Mo: What’s exciting to you about your current work?

Nick: What excites me is what I'm doing. I will occasionally see other people's work that I like. Admittedly, we're friends, but I like the new Harmony Korine book that Gucci put out with him. That's an interesting photo book.

Nick: I was looking at some Nicholas Nixon books the other day that I haven't looked at in a long time. They're really good. I'm trying to get back into using my 8-by-10 again to photograph people with it. But I've been using the 6-by-9 format again for the last three or four years extensively. Those two books coming out were what I used my 6-by-9 with, so I thought maybe it's time to get the 8-by-10 out, so I bought another one so I can have one here and one in England.

Carbon monoxide poisoning (1994) from ‘Double Dactyl’, 2007.

Mo: Is there a medium or process that you want to explore with the work that you haven't had the chance to utilize?

Nick: A lab in London that did a lot of fashion photography closed in 2008. All the fashion photographers that didn't want their negatives, which was a lot—maybe millions—so I took them all and I have them in storage. I want to start printing them! I want to make work out of all these discarded C-41 negatives. I don't know how because I don't have the time, but I would really like to get into these photographs. I'm sure most of it is terrible but there must be something there. I printed out about 20 of them to do a project with David Shrigley but that never went anywhere, unfortunately.

Mo: Are there any artists that you haven't worked with yet that you want to work with?

Nick: I'd like to work with all sorts of people if they were interested. Collaboration is good if you agree to do something neither of you have done before. If you do a collaboration where you're enhancing what one person or the other person does then I don't really see the point of it. I'm always open to collaborations but I haven't done one for a long time. I've done one with Irvine Welsh but that project hasn't seen the light of day.

Mo: Are there any you've done memorable to you now?

Nick: The most successful collaborations I've done are with Miguel Calderón, the Mexican artist, which you can see in various places. And then I made a film where the band Orbital did the soundtrack.

Rock Pool #1 (2004) from ‘Double Dactyl’, 2007.

Mo: Do you have any burning questions about art or photography that haven't been answered yet?

Nick: Yeah, otherwise you wouldn't keep doing it. It's an ongoing exploration where one thing leads to the next which leads to the next. The trouble with me is that I only really like making the work, and then I'm really terrible at getting the work out there. I'm always making the next thing, so most of the work never really sees the light of day. I don't have a gallery so there's no one else promoting it for me, so it's about what I can manage to get out there. Obviously, for people who are better organized than me, more things happen.

Nick: I like to wake up in the morning and ask, “What am I going to do today?” If I have to wake up in the morning and I know what I'm doing every day for the next six months then I would hate that. I'm not going to wake up and have a day off where I'm feeling lazy. That never happens.

Mo: So you desire spontaneity?

Nick: Yeah. I like to wake up and see if the weather is good, then I'll take some pictures. If it's raining then I'll go to the studio and paint. I don't operate commercially as a photographer but I'll do the odd job every now and then.

Mo: Is there a reason why?

Nick: I think it fucks up your creativity. I have a couple of people who will occasionally give me jobs that know what I'm like, so they're not going to expect me to be someone I'm not. I'll give them my time and put 110-percent into it, but I'm not going to want to go and have meetings about it weeks before or weeks afterward. I turn up, do it, and move on.

Hackney Riviera

Published by Jesus Blue, 2019

This series came together organically as I photographed my London neighbourhood throughout last summer’s World Cup. Most of the images were made at a secret swimming spot on the River Lea in Hackney. I see the work as a metaphor for the merriment and positivity of the British people at a time of turmoil and indecision caused by Brexit.

Words by Nick Waplington

Mo: How do you know when a photo project is finished?

Nick: With a photo project it's when you get to the point where there's too much repetition and it's not really going anywhere. With a painting, you kind of just know when the painting is finished. Sometimes if you go a little bit further the painting becomes ruined so you destroy it.

Mo: Are there narratives that your paintings communicate that possibly your photography can't and vice versa?

Nick: With a painting obviously the canvas is empty and you fill it. And with the photos I take the canvas is full to begin with, so maybe you're trying to take things away from it to simplify it. They're diametrically opposed, therefore, it can it interesting to work on them together.

Mo: What is work that you've completed that has changed assumptions you've had or assumptions people have had about a certain topic or theme?

Nick: I'm interested in everything, to be honest. Sometimes you make work and you think it's about something and then you realize two years later that it's actually about something else. So then when you put it out into the world, and when it's contemporary it's about one thing. But as time moves by the work becomes historical and the meaning of it can change. What could look quite interesting to begin with sometimes can become boring, or not. You can put the work out there and it can mean whatever people want it to mean.

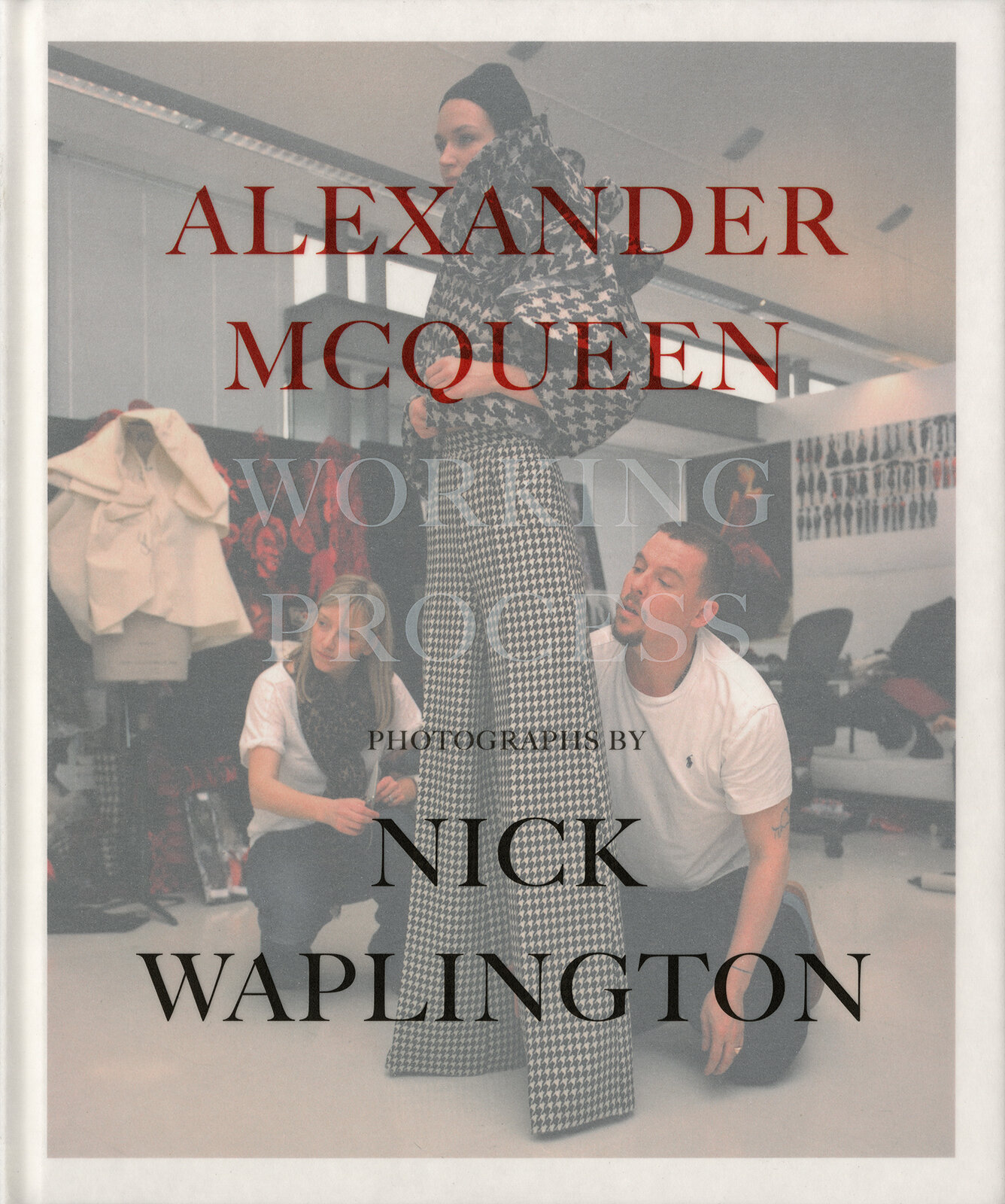

Mo: Were you surprised at the reaction people had when your McQueen work was published?

Nick: When I made it he was alive and by the time it was published he passed. What's happened with that is he's become this mythical figure in the fashion world. It was a very good book, I think, and it really gets to the essence of him as a person but also his working methods and fragility as a man. Obviously, people want to know about him so they ask me about him from time to time. I'm not a spokesperson for him, but fortunately or unfortunately I do have this body of work, and I was friends with him so that's going to happen. People ask me about him and people ask me about Avedon.

Nick: Avedon died nearly 20 years ago, so for a lot of young people Avedon is this kind of mythical figure from the heyday of his work which I guess was the '60s or '70s. Obviously, I was kind of involved with him so it's not surprising when I'm asked about him and I try to tell them what I can.

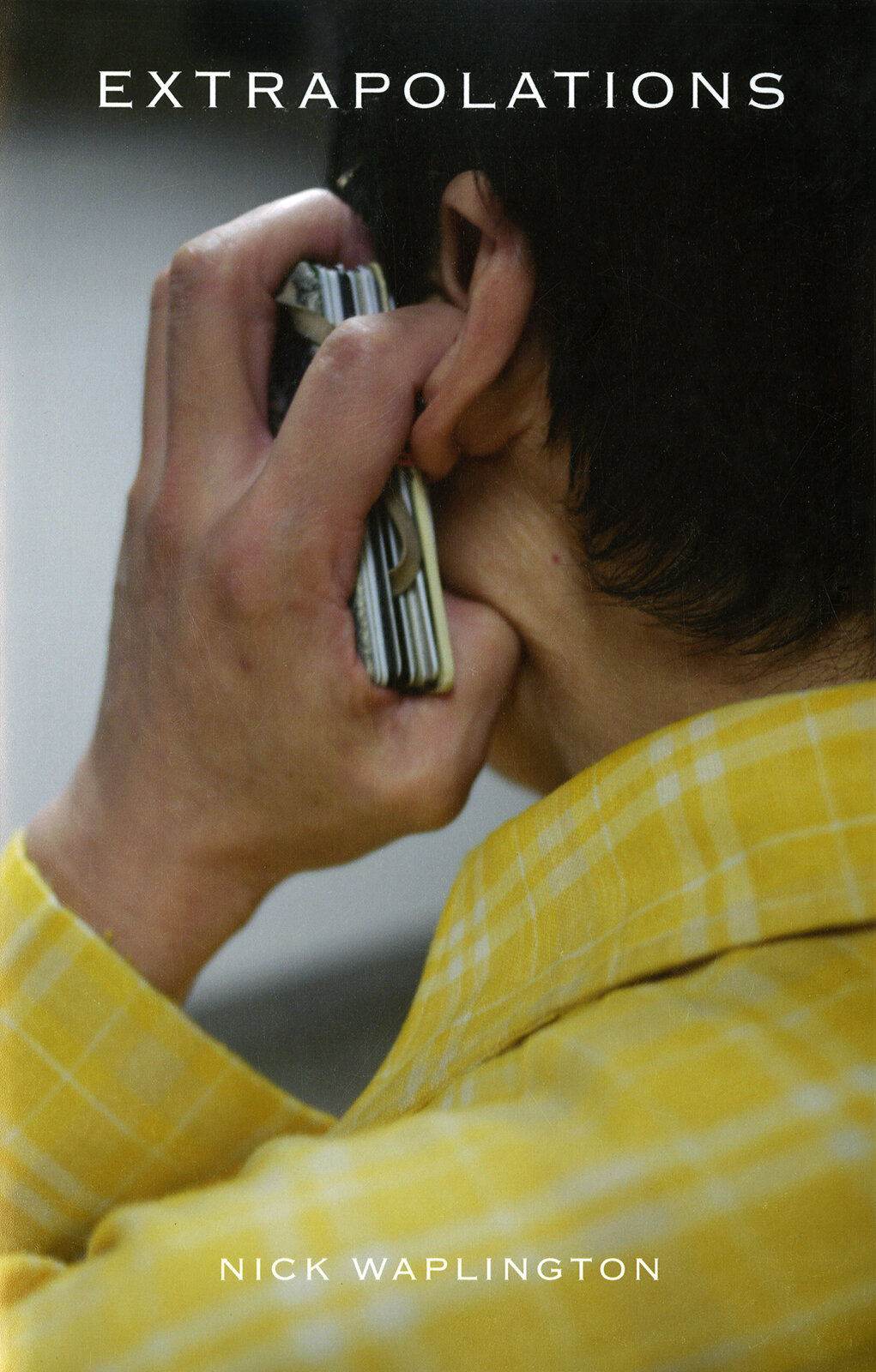

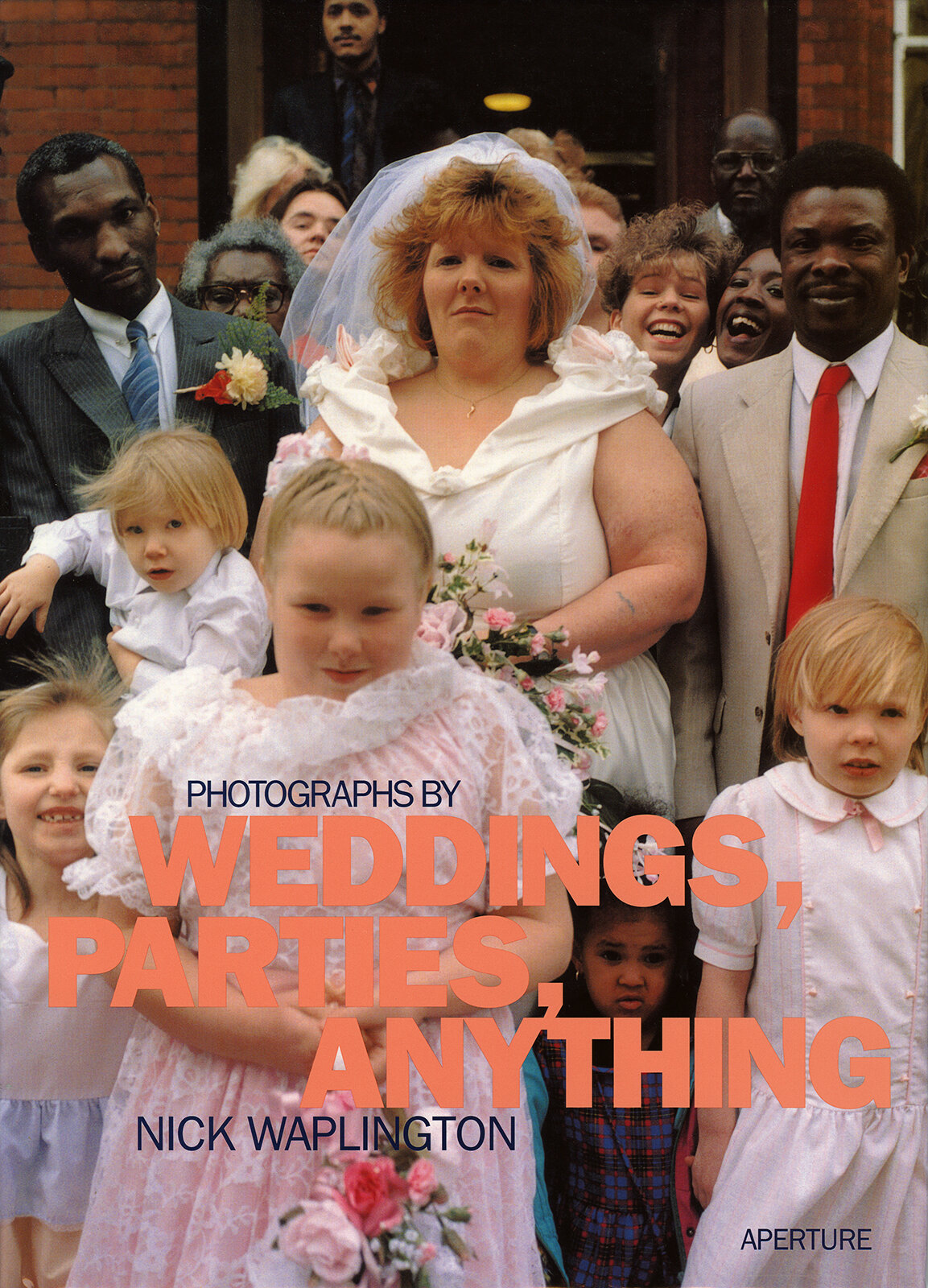

Select Publications

1996 - 2020

Mo: Is there any past body of work that you want to encourage people to explore?

Nick: The work that I made for the Venice Biennale about the internet in 2001. I didn't realize at the time that when I made it, people weren't really using the internet like I was. I feel like the work was kind of ahead of its time so I wish that it got more of a shift then. It was good of Harold Szeemann, the curator of the show in Venice, to include the work and there's a big book from the project called Learn How to Die The Easy Way. [both laughing] You can buy it for five bucks but no one's interested in it!

Mo: What do you feel is the purpose of your work right now?

Nick: To keep me from going mad, really. It's so I can get up in the morning and have something to do. It keeps my mind off things. I'm not very good at getting the work out there—I never have been. There's a huge gap between where I'd like the work to be and where it actually is. We live in a world where promotion is important and I'm terrible at that.

Mo: It's almost like an art at this point.

Nick: People are out there making shit work who are super fucking famous. Once, I was like, “Wow.” Now I don't care. I've accepted that I’m always going to be an underground artist, as you call it. It's another way of saying, “a failure.” [both laughing]

Mo: Regardless, it seems that you're very confident in your work.

Nick: You have to be confident if you're going to put out the work. Some of the things I know aren't the best things but I still put them out there because we live in a world now where people are trying to make perfect objects or perfect pictures. Everything is very aesthetically perfect and I know historically that those types of works, in the long run, will be the work that is rejected by history.

Nick: I think about when I was young and I was first going around the New York galleries in the early 1980s, there would be all these shows with big abstract expressionist canvases of people you've never heard of now that had whole page adverts in Artforum. They've all disappeared.

Nick: But then you've got David Wojnarowicz, who's made collages with newspapers in his shitty apartment in the East Village, and that gets the big show at The Whitney. That was a kind of Lo-Fi East Village art. You got the slick and clean work that was very important at the time because galleries can commodify that and sell it, especially if the artists—the people who are making it—are good at operating that, but that's not necessarily the most important work in the long run.

Nick: I've got to have the confidence that an outsider like me is maybe doing more important things than things that are at blue-chip galleries. Maybe I'm wrong, but I probably won't be alive to find out. I just have to stay true to what I'm doing and believe in it. It's been over 35 years since I've been doing this.

Mo: How do you look at the future of your work?

Nick: You just take it one day at a time. I don't have any big plans for the future. If I'm still alive in five years then I have no idea what I'll be making then.

Mo: To round this conversation out, is there anything someone has said to you that you've stuck with that's fueled your work?

Nick: Someone said to me to make sure that you've eaten properly before you start work. And enjoy the work. If you're not enjoying it then there's not much point to doing, otherwise, you might as well be working at Amazon loading up the carts. 〄

Read On

- Viewfinder

Conversations that explore the risks, ideas, and experiences of ones practice.

- DIGITAL DISCOURCE

Live chats between artists that share thoughts related to their practice.