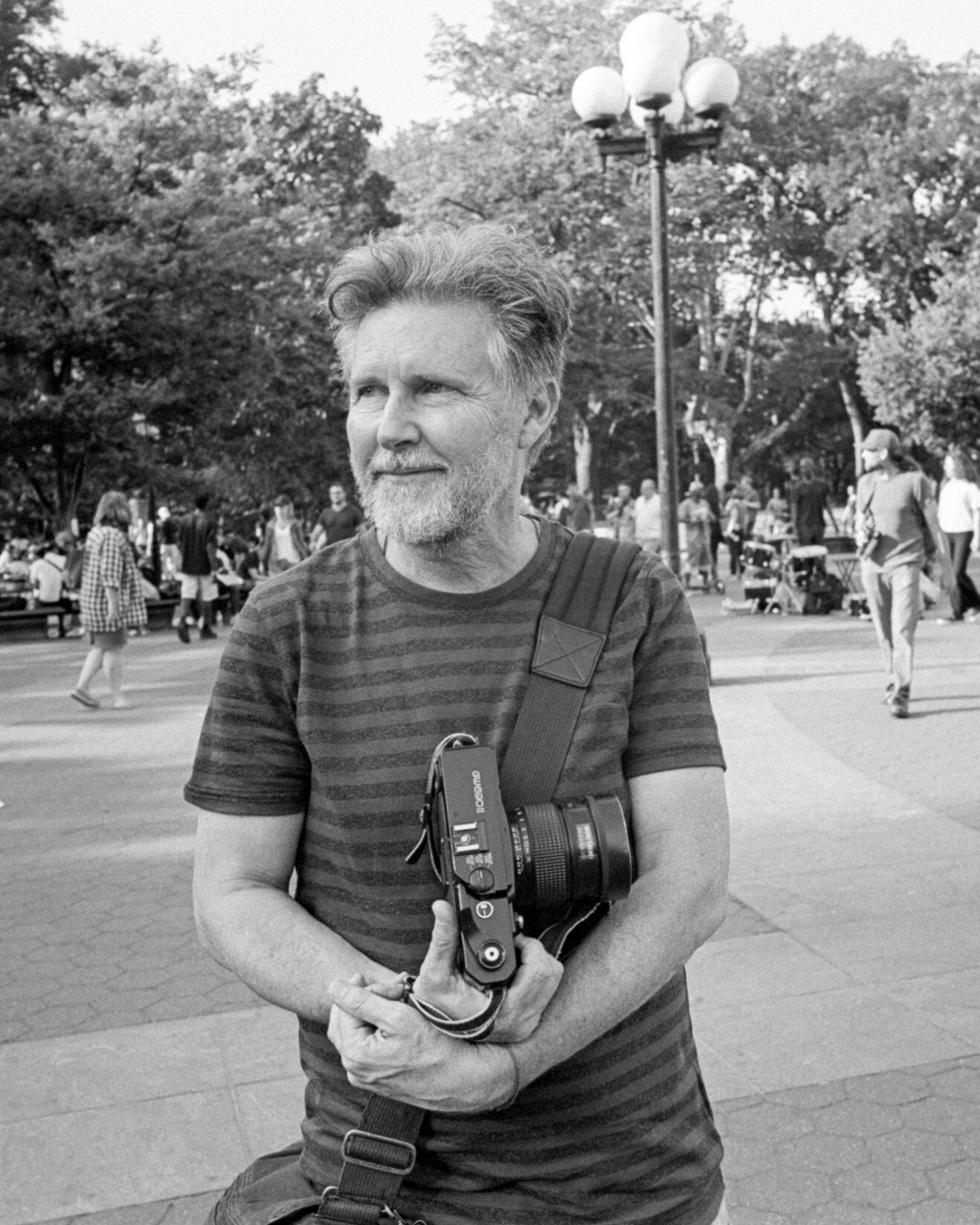

Mark Steinmetz

For Viewfinder

An exchange through photography.

Portrait by – ANDRE WAGNER

Mark Steinmetz has often been described as a photographer who photographs the “ordinary,” but when looking at his photographs one feels this characterization doesn’t approach what he’s accomplished. The subjects in his photographs may be ordinary, or as ordinary as anyone or anything is.

In fact, when considering the people in his pictures one might imagine that they are waiting to meet a friend, are about to go home for lunch, or are just plain lost in thought, and the landscapes might otherwise seem unremarkable or common. But when Mark turns his attention to them, they seem to belong to him and through his lens, are relieved from their ordinariness. They are now described in what seems like a thousand shades of grey, existing in a glowing halo of sensuality and grace.

Looking at Mark’s photographs is a reprise from the ordinary in the best possible way. The viewer is immersed in an almost mythical narrative of his making, exuding an understated beauty anchored in the very familiar.

A friend of Mark's

By Mo Mfinanga

December 9, 2019

Estimated 24 minute read

Interviewed at Washington Square Park on a warm Sunday in late September.

Mo: Is there anything new in photography or life that has been injected into your work?

Mark: It's hard to say. I mean, photography and my life are inseparable—it's what I do. It's given shape to my life. The particular place I’m in is because of it.

Mo: Do you feel like that place you're in has always felt the same, or have things shifted a little recently?

Mark: I have a baby now—a 2-year-old. Donald Trump is in office. [all laughing] We’ve entered a parallel universe here. I have a lot of books coming out, I'm looking over old work that I had no idea about, and Robert Frank has died so it's interesting to consider what I was doing and where I am now. Maybe this is a reflective period.

Mo: Have you thought about legacy recently?

Mark: I've always thought about the long term. Legacy seems a little egoistic but when you read Robert Frank’s obituaries and see everything pouring in you might consider legacy a little. His work mattered to many people. You just want to make good work that hopefully will be retained but whether that happens is not really in my realm or anybody else’s realm. There's all this junk that people keep jumping up and down about and maybe they’ll keep doing that forever. You have to feel like you've done a good job and maybe the world at some point in time will look at it and come to value it.

Mark: I take photos to share them. Photography’s a system of sharing. You take a picture in one place and in one time and then it's fixed. It can then be shown and reviewed by somebody else somewhere else. For Frank, he was hitting this feeling, this note. I'm sure he knew it and that's what he was offering.

Mark: All bets are off, really. Trump being the president is beyond anything I could imagine. Art is becoming more and more [pauses] political... The work I see on gallery walls doesn’t look like it was made by artists having all that much fun... Why aren’t the artists having a blast? It's like the critics, theorists and curators have won some sort of battle; the artist and poets are now secondary.

Andre Wagner: I think it's also up to the artist, too. Why is everybody giving in? When did that become the cool thing to do? It's strange.

Mark: It's strange to me. I think money is a problem. You need to make money in New York City to do this so you do things that are going to please others and succeed in the money arena. When Robert Frank was here I think you could get by with hardly any money. Things were different.

Andre: There's still sacrifices people can make. I remember years of eating dollar slices of pizza so that I could buy a couple more rolls of film. There are things you just do because you don't want to bend and mold to this other thing.

Mark: Exactly. You got to be very smart about planning your resources. And you're right, whatever it is, it's gotta go into film; it's a sacrifice. It's deciding that this is more important than this. If you develop your film, you don't want to just take junk all the time because it's your time. Instead of having your cappuccino or whatever, you've got this extra roll.

Photo from “South East” (2008).

Mo: Do you have a certain resonance with fall? If so, what does that entail?

Mark: Absolutely. The light is lower which has a quickening about it—the sun moves quickly. And there's a melancholy feeling. The leaves fall, the light becomes crystal clear and it's warmer than winter where you also have low light. Fall has always been good. September, October—people are out. I can’t believe I’m quoting Yoko Ono, but she said, “Autumn passes, and one remembers one’s reverence. Winter passes, and one remembers one’s perseverance.” And I say summer is a great time for a siesta.

Mo: I’ve talked to Andre about how he works around the cycles of the city. Say, eating his lunch before others so that he can capture people in the city at that time. Do you have a similar approach?

Mark: I agree with Andre—the early bird catches the worm and you have to be smart about your timing. I think “cycles” is a good word. There are always rhythms. I think the time of day and time of year are beautiful things to describe. If you have a picture of a person, then great, but how about also having the season the person is in. A little context can flip everything over.

Greater Atlanta

(1994-2009)

"Greater Atlanta" is the third book in Mark's "South Central" trilogy. This book is the result of Mark photographing Atlanta and its outlying regions.

Mark: I just want to say I was born in Manhattan. I'm one of the few people who's a real New Yorker here. I just see all these posers. [all laughing]

Andre: Where were you living before Athens?

Mark: Chicago, then Knoxville. I was bouncing around a bit. I had been in Boston.

Mo: How long were you in Boston?

Mark: I was there a few years after graduate school. Three years ago I was there for two years, too. My wife was working there.

Mo: And you went to Boston from LA in the ’80s, yes?

Mark: I left New Haven for LA in 1983. I was in Boston in '86 and '87. I had been in Chelsea (Mass.) which was a total dump then. In Boston, art directors wouldn't pick up the phone. I'd call and say I was a photographer and that I’d like to show my work, or you could never find parking. Since I was in Chelsea—and there wasn't the Big Dig yet—if you didn't leave Boston by 3:30 p.m., you wouldn't leave until 8 o'clock because traffic would be so bad. I left Boston for Chicago in 1988 and there you could park easily and art directors would be happy to meet with you.

Mo: Do you feel like Georgia will still be the place for you in the near future?

Mark: I don't know, we've got a great setup there. We're starting this thing, The Humid, which is where we offer photo workshops. Curran Hatleberg, who's in the Whitney show, he and Matthew Connors are going to give a workshop in November.

Mo: What have you learned from the people who come to the workshops?

Mark: I think it's good to touch base with other people and see how they think. For me, it's been good to become a better explainer of ideas. People are nice, it's fun, and most of the students, especially lately, are graduate-level students. I see them around and they've been publishing their books. I’ve also been teaching at the University of Hartford in their graduate program. Their program is very book centered. And I’ve also been a critic at Yale.

Photo from “Angel City West: Volume One” (2017).

Mark: I try to be economical in photography. You don't want to overdo things.

Mo: What do you not want to overdo?

Mark: Overdoing would be too many photos in a book; too little subtlety in the photos. In photography, Eugène Atget is a great example of being somebody who was super economical. He's making his point directly with clarity and ease. I think Garry Winogrand is economical and his frames are packed. Lesser photographers have many things happening in their frames but it's not music, it’s just very busy.

Mo: Did you learn that directly from Winogrand when you were with him?

Mark: I learned everything from his pictures. I learned a lot from meeting Winogrand—just from his way of being. But I don't want to say that he put his arm around my shoulder and said, “Hey, you gotta lower that frame a little bit and get your knees down.” [laughing] He didn’t talk much about photography.

“Why stay small if you’re really curious about something? The thing to do is to be true to your nature and follow your curiosity.”

Andre: I wanted to ask your thoughts about the teaching. Is it something you've always been interested in? You've been taught by work, so I'm curious how that feels when you're teaching?

Mark: Most people have some confusion. You can just tell what it is about what they're doing that's good. You can also help them see something where it's like, here, you're committed; here, you care, you're alive and it's working. Whereas here, there's a little bit of a false note; you've seen too many pictures, and you're kind of wishing. I think it's helping people, at least through their photography, to find their natural vein which is satisfying to me.

Mark: I don't want to teach a class where I'm taking attendance, giving grades and the students don't fully want to be there. I prefer when people know where I'm coming from and I don't have to be with somebody who would rather be doing fashion pictures or something commercial—but overall it's been fun. You have to make a living somehow; nobody is paid just to think. You're paid for services or products.

Mo: What has shooting fashion shown you that your personal work hasn't?

Mark: It's just curious to me when people ask me to do fashion. [chuckles] Okay, I get a trip to Paris out of it! It's fun working with a team. I've seen a lot of fashion pictures where I think it would be interesting to do my version—I would do things differently.

Mo: Is there any other landscape of photography that you've been curious about?

Mark: Nothing in the commercial vein. If I had a super long life, I'd be interested in a few years of night photography and seeing what I could do with a super long telephoto lens. But I'm pretty happy with this game of, “Here you are with your two legs and here's this world, and nobody knows who you are.” There's no special access. It’s the flaneur and auteur mode I suppose.

Select fashion work (2015-2019)

Andre: When you said being around Winogrand affected you, is there any other photographer who you were able to be around physically that had the same effect?

Mark: I think Thomas Roma is a challenging photographer. Richard Benson was influential and principled—always taking a long view of what's going to last. It's helpful to know people who actively photograph. But the main thing I think for me is knowing that there are people out there who can discuss photography intelligently. Having been to Yale, Tod Papageorge talks about Cartier-Bresson or Atget and the work takes on an added dimension. The old MoMA photo department—Szarkowski, Galassi, Kismaric—all have been helpful. But it helps, too, to have your work published and shown. Putting out work helps you to put out more work and you shape your own context over time. I think that it enables you to take more pictures but also pictures that are maybe self-referential.

Andre: As far as publishing?

Mark: Yeah, you put your work in books and you can start weaving a wider web.

Mo: Are there any recent bodies of work that you've learned from?

Mark: 42nd Street and Vanderbilt by Peter Funch is one, not that that is work I would attempt. And the same thing with Paul Graham’s recent books. You can return to books and study them. A show is something that can make an impression but you can't take it with you. You leave with a sort of vague remembrance.

Summertime

(1984-1992)

"Summertime" is a series of portraits of kids and teenagers caught in the midst of activity in distinctly American settings.

Mo: What are, if any, burning questions you have about photography that hasn't been answered yet?

Mark: Not sure about “burning,” but I guess I wonder about the lineage that I'm most interested in: Evans, Franks, Friedlander, Winogrand, and a few others. People think so differently now. I have questions more about the audience than the medium.

Mo: What is it about the audience that you're curious about?

Mark: That people voted for Trump, for instance. Is the human race ever going to change or do we remain mediocre? In terms of photography, I wonder whether there will be an audience or forum for ambitious straight photography and how large it will be. Will the tradition collapse?

Mo: It's interesting to see where art exists within that political air as we talked about earlier.

Andre: It's not even just about political art, but I think it's just the straightforwardness—being spoon-fed.

Mark: Its propaganda. I want to see minds get freed.

Andre: This is super wide, but how much do you think the internet has had to do with the shift?

Mark: I can’t say. For me, the internet's been great. People I don't know can blog about the work so we no longer have the gatekeepers, the bookstores and publishers who have typically had all the power to determine everything. Across the world, you can have colleagues and peers and I think that's great.

Mo: We've never had this much access to share narratives before.

Andre: I think that's the problem. Who am I to say, but maybe someone sees such-and-such doing that and then that such-and-such has 200,000 followers and they have some brand backing them. All of a sudden that's what you want instead of thinking for yourself and working for yourself.

Mark: Time and time again you have somebody mediocre lecturing and the room is full and then over here you have someone truly excellent and only a few people. It's not anything new. [laughing] But look, Patti Smith is running around and people listen to her.

Mo: There's this conditioning of short term thinking.

Mark: But that's something you can talk about as a teacher. People have to think more about the next step. It's like coaching. Every stage of life things change so you have to adapt yourself. I like watching tennis and you see Robert Federer getting older and at a certain point, he spends a year changing his serve. It's a little wobbly at first but then it makes sense—like a baseball pitcher once he’s lost his fastball.

Mark: You can run around the world in your 20s. In your 30s, you've got a few more responsibilities and you’ve got to be more targeted. And then, later on, you go more directly to your subject because you can't run around all the time, but there are different advantages as you age. When you're older maybe you have more wherewithal to have access to some privileged places. [However] I'm still all over the place. [laughing] I'm traveling the world more which is weird. I was in Central Asia making work and I'm going to have a book about Berlin come out.

Mark: I don't think I can finish this project but I was interested in going around cities in the world and photographing in these kinds of nondescript, regular urban spaces and photograph pedestrians and people on the street—nothing touristic or exotic. I just want to photograph contemporaries of mine on the planet in these city situations. We were in Kyrgyzstan and that was interesting—that was a different movie. And then Uzbekistan is maybe more like what Italy was 40 years ago. You can do these photos of modern people in quasi-ancient contexts.

Mo: I wonder if there's a thing you think about when going to various countries where you're the minority.

Mark: I don't think about what they make of me because that would be very tiring. To me, I'm at this stage of life and I've trained myself. Looking at my contemporaries in other places, why not do that? A lot of political correctness is a bunch of shoulds and should-not. I don't see why I wouldn't have access to another human being on some level. Half the world believes in reincarnation and so maybe you've popped in and out of other races, genders and cultures before. Maybe you bring some of this knowing with you in your current life.

Mark: We're all part of this collective. It's a question of belief. If people believe in divisions then you focus on that and have that. Walker Evans said, “You live once so listen, eavesdrop, stare, just to know. Life is short, die knowing something.” Why stay small if you're really curious about something? The thing to do is to be true to your nature and follow your curiosity.

“Work should be open-ended but you need to nail that ambiguity just right.”

Photo from “Berlin” (2014) published by Kominek.

Andre: These recent places you've been, have you gone on your own or were you teaching there and started making work?

Mark: Yeah, in Shenzhen, China I was teaching wealthy Chinese high school students and it's right across from Hong Kong so that was interesting. In Berlin, I'd been teaching there for a week every year and I'd stay longer. I did some meditation workshops in Peru and Costa Rica.

Mo: Have you always meditated?

Mark: Not always but I've done it now for over 20 years. It's good to go in a group or have some facilitator where you can go deeper. You then take that with you when you practice on your own.

Mo: Are there practices within that meditative state you've found while photographing?

Mark: There's the whole mindful practice. You want to be awake while you live your life. I think it's very good for photography, especially for fairly fast photography. Time is stretchy. You breathe, you don't panic, you're just conscious and aware and then you take the picture when it's right. The whole idea of having a digital camera on a motor drive and then you just select the best one, it's like why though? Don't you want to be the master? Be like Luke in Star Wars. “Use the force.” [all laughing] You want to embody it. Photography is not just about making the picture.

Mo: And you don't surrender to your tools completely.

Mark: Well, you don't want your tools to overwhelm you and be in charge of you, but you do want to surrender to the world and the flow. You want to accept the tool that you're using and not wish it were something else.

Mo: Do you feel like photography was the first medium that allowed you to surrender?

Mark: There's one book I read, The Inner Game of Tennis, and it's really the same lesson as Zen in the Art of Archery. If you move your body around to the right spot you can always hit that forehand and you can always hit that backhand, and you can always hit that serve. A lot of it is about choking. [laughing] A lot of great players are out of their bodies. It's phenomenal the speed at which they are reacting. They are letting go. They're not thinking of how they have to move. They're in it. Photography is the same.

Andre: I grew up playing basketball and when I look at it now I consider that to be my first art form because drawing that parallel of trying to master the thing so you can be on the court and you're not thinking about being in that passing line. It all just happens.

Mark: It's being natural. You don't need your mind. Engage all your senses and be alive. Friedlander said somewhere photography is a lot like athletics and I agree. You've got to be in good shape and if you enjoy moving your body, having played basketball, then you're going to be so much more sensitive to other people's gestures and movements.

Photo from “South Central” (2007).

Andre: I know in your earlier work you were working with the 35mm talk about this sensitivity. So how did that sensitivity translate to when you started working with a different camera?

Mark: I think using the 6-by-9 was kind of for the resulting print and the light. I guess I wanted to shake things up. I wanted to make much more compressed, focused pictures but where something was still happening, a movement was arrested. With the 35, I'm kind of done, just cause of Winogrand. He put a pause on it for everyone but I think over time things have changed enough and maybe it’s time to return to 35mm. I think you have to keep at it. His late pictures, I guess, are controversial because other people are editing them but the ones I've seen are fantastic; they're strange.

Mo: In what way?

Mark: Strange in their departure from he had been doing. They're doing more with less. There's a little bit more of an adult energy, a weariness. I'm interested in photography—and so was he—where you don't know how it works. Eggleston does that in his best work. There's a certain mood. Work should be open-ended but you need to nail that ambiguity just right.

Mo: Did it take other people to make you aware of that?

Mark: No, I think in the LA work—the Angel City West books—it's all about play. I have a frame and I'm running around and it's sort of, "What if?" Putting these certain facts or particular things within a frame and seeing how they relate, do they add up to make some kind of story? And what kind of story is it? I think that was the aspect of photography I was most interested in.

Mo: Is it still the aspect of photography you're most interested in?

Mark: [laughing] I think so.

Carnival

(1982-2001)

Mark traveled to country fairs, urban street fairs, and small circuses across the United States, to make photographs of the families, teens and carnies that contain all the warmth and frenetic energy of a day at the carnival.

Andre: What's like when you go to edit? Are you looking at your negatives?

Mark: It takes a lot of time. I think I'm a better editor the more that time has passed. I mean, I'm out photographing, I'm on my path, and I take a certain picture and I don't know what for, especially for the ones in Greater Atlanta. There were all these pictures and it took a while before I realized what I was doing. I had some kind of plan but when you finally see and get what you're doing, you see that you had been doing it for quite a while. You're trying to do something new; you're trying to come up with a new language. It's a lot of sweat and confusion, flipping around and flopping, and excitement.

Andre: How do you know when it's finished?

Mark: Basically when the energy has subsided. I have a book on carnivals coming out and I remember I was taking pictures of carnivals and fairs and thought this was sort of an easy, familiar subject for a photographer but apparently not many people have done it in a sustained way. I thought I would just be photographing at fairs throughout my life but then I sort of just stopped going. I picked up the carnival theme from time to time and then forgot about it. Then a publisher asked if I had more pictures of fairs since I had done a previous project with them, and there were a few fair pictures that we had edited out. Then I realized that for years and years there were these pictures! It's a book that's big and heavy and weighted towards the ’80s and ’90s but there are some from the ’00s.

Mo: It's interesting when you're revisiting a body of work without there being an expectation.

Mark: It's a good time in my life for me. I have an ample house, the darkroom is good, I've got an assistant and now we have digital technology. I'm used to making physical contact sheets and now I have an assistant who makes digital contact sheets that can go into Dropbox. I can be on the train someplace and edit. So this is some freewheeling dream come true! Hats off to Friedlander because of all those books, like The American Monument, where there's tons of pictures and he's shooting everything all at once, he then has to somehow edit and pick out The American Monument pictures. He's a huge cataloguer. So anyway, I'm using Lightroom and it's so much easier. [all laughing]

“You want to find that fire in you, keep that lit and let it lead you. It’s not about some praise from this place or that person.”

Mo: What is the most ongoing challenge or risk you take in your work?

Mark: I believe there needs to be this feeling of risk in the work or you don't have passion. But the risk has to be like when you're in high school and you're asking somebody out to the dance. [chuckling] I think taking pictures of people is a risk. You can't explain that well why you’re interested and your reasons might not be so clearly noble, or maybe they are but you can't explain it in simple, clear terms. It's always about celebrating and honoring, but people tend to think that has to look a certain way.

Mo: What do you feel like the purpose of your work is right now to either you or the world?

Mark: I can't take responsibility for how the world is going to receive it. For me, I'm making pictures the way I would like to see them made. Sometimes people make pictures where I love what they do and it doesn't have anything to do with me. But I think, again, it's sort of back to sharing. Robert Frost talks about poetry as a momentary state of confusion. There's a great essay by him called The Figure a Poem Makes, which is apt for what makes a great photo work. It's always a challenge to make something that works. For me, it's more about bodies of work; it's how all the images interlink and affect one another. Basically, it's to reach somebody and maybe help them have a momentary stay of confusion.

Mo: Is there anything someone told you that guided your practice in some form?

Mark: With Winogrand, we didn't really talk about photography much. He once said, “The world is full of seductions.”

Mark: There's some Greek fable where there's the most beautiful woman in the world and she's got these golden apples. She’s a fast runner and if any man can outrun her, she’ll marry him. All her suitors are chasing her and they really want her but she drops a golden apple every so often so they stop to pick them up. But in picking up the golden apple, they've lost their chance. You have to watch out for what you're going to let distract you from your work. Why are you going to lose yourself because of some material or status thing? You want to find that fire in you, keep that lit and let it lead you. It's not about some praise from this place or that person.

Mo: How do you embed that?

Mark: I’m not sure. Try not to get seduced. Maybe all of a sudden I'm playing badminton three times a week and getting a bit carried away and getting into great shape. [laughing] I did some color photography for a while so you kind of go off track a little bit.

Mark: Sometimes you have an awakening and realize what you’re doing is not as vital as what you could be doing. 〄

Mark Steinmetz and Mo Mfinanga by Andre Wagner.

Discover More

- Viewfinder

Conversations that explore the risks, ideas, and experiences of ones practice.

- DIGITAL DISCOURCE

Live chats between artists that share thoughts related to their practice.